Now that the Buntport Theater Company is winding up its tenth season – filled with remounts of several past shows – it’s time to stop thinking of this troupe as talented kids who got together at Colorado College to create a theater style all their own, and instead consider them the creators of a distinct body of work. Still, it’s hard to generalize from the year’s mix of staged readings, extemporaneous evenings and full productions culminating in the current offering of two early one-acts which – as the program helpfully points out – have nothing to do with each other: And This Is My Significant Bother (2000), a series of scenes based on James Thurber’s short stories, and an insane, babbling interpretation of Cinderella (2003). You can pinpoint specific Buntport tendencies: clever work with objects; playfulness and humor; an inventive approach that continually constructs and deconstructs the very idea of theater itself; a love of language that means the Buntporters’ favorite writers, from Melville to Kafka, are treated with a wonderful mix of cheeky overfamiliarity and profound respect. This company likes dramatizing odd fragments of fact they come across: for instance, the trauma suffered by the poor brontosaurus after it was demoted and renamed by scientists (The Mythical Brontosaurus); the obsession of one Wilson Bentley, who spent his life photographing snowflakes (Winter in Graupel Bay); the actions of Niyazov, dictator of Turkmenistan, who upended all notions of truth and time in his country, in part by renaming the months of the year for himself (The 30th of Baydak).

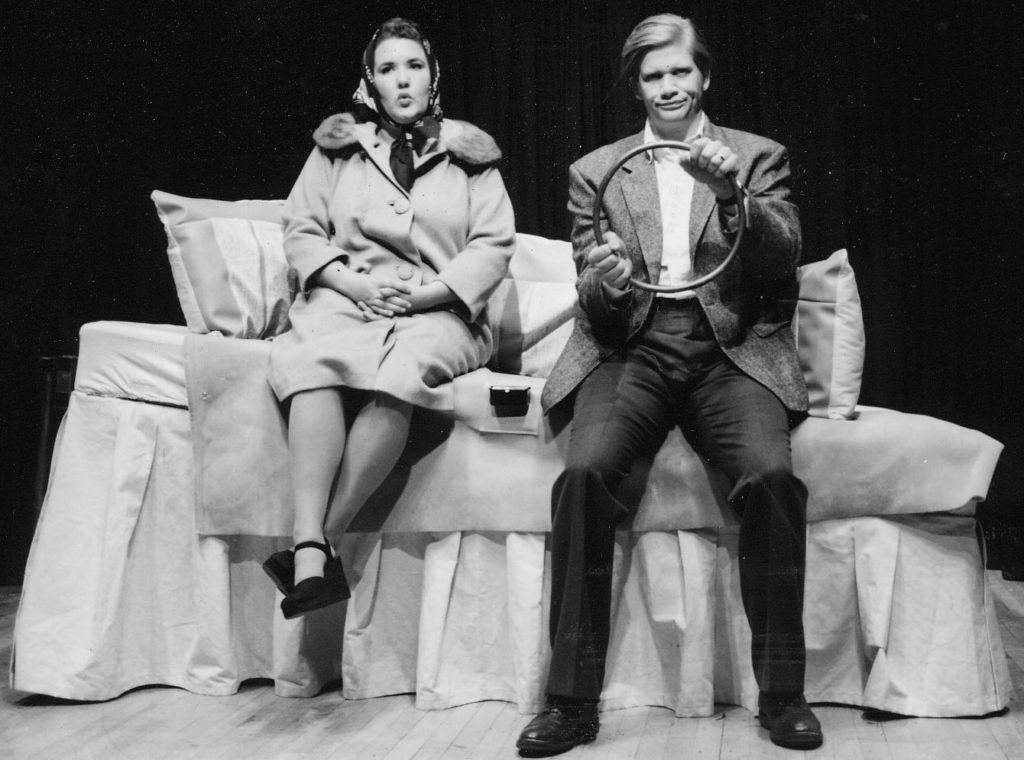

At the beginning of This Is My Significant Bother – which was Brian Colonna’s senior thesis – four actors are lying on a large bed, their left arms over the coverlet and perfectly aligned, each wearing a wedding ring. James Thurber didn’t have a very positive view of marriage. His men tend to be put-upon dolts and the women bossy harridans. The tone is slightly waspish, also sad and, in an understated way, very funny. The actors – helped by the music of the Hoagies, who play things like “Making Whoopee” and “Two Sleepy People” – have caught it perfectly, giving their portrayals a sort of stubby elegance.

A man kills a spider at his wife’s behest and then huddles under the covers, terrified by a flittering bat; a couple argues in their car about where to eat and whether Donald Duck is a more significant cultural icon than Greta Garbo; a husband decides to kill his wife so he can marry his stenographer, and the wife, having gotten wind of this, tells him exactly how he’s to do it; a divorced woman fills in her successor on all her ex-husband’s idiosyncrasies while he silently and meticulously makes up the bed. And there’s a touching story about a failed love affair, the sentences punctuated by silences and blackouts. If this is an early effort, you can’t help reflecting, it’s certainly a sophisticated one.

Cinderella is an extended piece of intense silliness, narrated by a be-rouged Evan Weissman in what can only be called Manglish; the rest of the cast speaks pure gibberish. The play begins when Cinderella’s sweet-faced mother (Erin Rollman) gives birth and almost instantly transforms into the Wicked Stepmother. She does this through a very clever costume change that forces her to walk backwards through the rest of the action. (Evil usually does occur when good is distorted or turned on its head, right? That’s why the word “sinister” is connected with left-handedness and the left side of things in general.) Doubling is a central theme in Cinderella. Both stepsisters are played by Hannah Duggan, wearing an asymmetrical wig and two different shoes. Erik Edborg, the tallest member of the troupe, is our heroine. He’s comforted in his sad predicament by his own left hand, which sings opera to him. When he’s dressed up for the ball, he’s represented by a simpering doll through another piece of costume magic. Weissman’s narrator becomes the Prince. The coach is signified by a pair of horses clipped to a hat, the importance of Cinderella’s leaving the ball by midnight emphasized by the clocks on the breast of her ball gown. “Your Feet’s Too Big,” the Hoagies sing helpfully, as an ugly sister tries to cram on that mythical slipper.

There’s no predicting what the next ten years at Buntport will bring, but we know they won’t be boring.

-Juliet Wittman, June 7, 2011, Westword