Enter the Mysterious, work is always newly minted, nonlinear, rich in metaphor and submerged — perhaps inarticulable — meaning. Still, I can usually ferret out some kind of narrative, even if it’s highly fanciful. But I could find no real through-line or progression in Buntport’s latest original production, The Crud, which is based on objects found in a storage locker the company bought last year. That’s logical, I suppose, since the play’s oft-repeated catchphrase is “Time passes,” after which someone in the four-member cast will inevitably observe that nothing changes.

Once a hippie friend told me of an experience he’d had while stoned. (As I’m sure you know, profound breakthroughs in understanding often occur at these times.) Michael was eating mashed potatoes, and he suddenly realized that when the potatoes were on the fork in front of him, they represented the future. As soon as they were in his mouth, they became the present. And as they slid down his throat, they moved inexorably into the past. The Crud is about time, too, and like Michael’s story, it shimmers with absurd but oddly bewitching meaning. (This same Michael, by the way, once found himself intolerably thirsty while wandering in Berkeley’s People’s Park. But somehow he’d forgotten the mechanism for drinking. How did you get liquid into yourself? He tried pressing his body up against a tree in the hope that its sap would flow into him. When that didn’t work, he sat down next to a young mother seated on a bench, picked up her hand, and tried to match the tracery of veins in his wrist to the tracery in hers. He actually tried this on a few people. This being Berkeley in the ’60s, all of them surrendered their arms quietly, with no sign of surprise or resistance.)

Despite the nonexistent plot, there’s nothing sloppy or tentative about this production. In fact, it has moments that hint at tremendous insight — insight you never quite get but know is hovering in the air between you and the playing space. The acting is brilliant; Brian Colonna, Erin Rollman, Hannah Duggan and Erik Edborg (the offstage co-creator is SamAnTha Schmitz) work together with the kind of rhythm and mutual understanding that only comes from long and trusting collaboration.

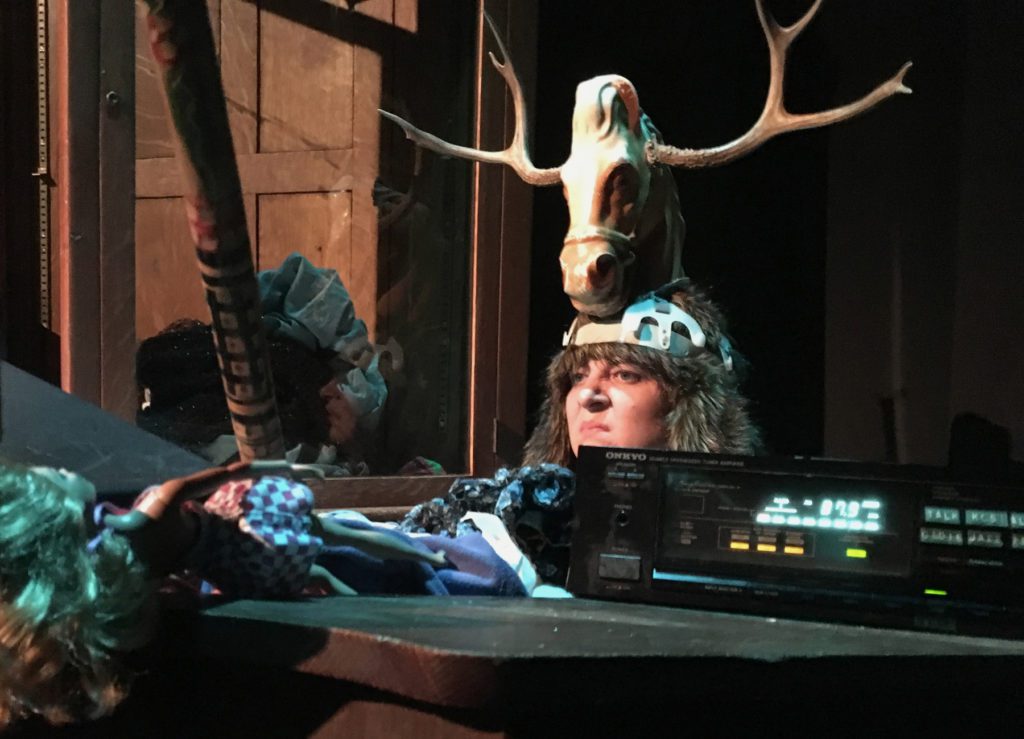

The crud itself is a huge pile of cast-off objects, toys and appliances belonging to three very peculiar people. First comes Barely Bear (Duggan), who’s covered in dolls and stuffed toys, including the Cookie Monster. Dear Deer (Rollman) wears a horned horse’s head and a skirt made of rustling newspaper and magazine pages that she occasionally consults. (This touch really speaks to those of us whose shelves are filled with old journals we can’t throw away because they just might contain some crucial piece of information.) Dear Deer has a constant craving for raspberry jelly; I won’t describe the revolting way she acquires it. Then there’s the Broken Baby Doll Detective (Colonna), who behaves like a Raymond Chandler character but carries an armless doll version of himself on his shoulder — the other, literal Broken Baby Doll Detective. The objects in the pile keep disappearing, and it turns out they’re being squirreled away by I Have No Name (Edborg) to a misty place of forgotten memories behind a scrim. No Name figures there’s no harm done because the other three forget these treasures the minute they’ve vanished. All it takes is the cry “Time passes,” and for them the world begins anew.

All confusion aside, it’s hugely entertaining to watch these amazing characters bicker, laugh, fight and give up, handle objects and explore their individual worlds. The visuals are stunning. The scrim separating present from past, and through which you see everyone’s actions slightly distorted, creates a misty, shape-changing, fairytale world reminiscent of the one Alice encountered once she’d climbed through the dissolving mirror in Through the Looking Glass. Those weird costumes are miraculously evocative. Dear Deer, with her thick-soled black boots and flowing black hair, sometimes looks like a warrior woman; at other times, she’s a peculiar little girl — cocky and full of herself, but lost.

This is Waiting for Godot as written by Edward Lear: a world of color, strangeness, mystery and nonsense that you most definitely want to enter.

Juliet Wittman, May 23, 2017 Westword