The five Buntport artists often create a full theater work based on a single eccentric premise: One of them saw Tommy Lee Jones standing in line for the Santa Fe Opera’s La Bohème some years back, and from that sighting emerged Tommy Lee Jones Goes to the Opera Alone, starring a giant puppet figure of the actor. When the group learned that famed scientist Nicola Tesla had been in love with a white pigeon, a kind of hybrid, multimedia play was born, though it enjoyed only a single showing. The gift of a slab of artificial ice gave Buntporters the cue for Kafka on Ice, a biographical piece that incorporated incidents from the author’s Metamorphosis and was performed on skates. But the idea that sparked the current offering, The Book Handlers, seemed on first thought particularly narrow. The Buntporters had encountered a satirical essay by an Irish writer, Brian O’Nolan, in which he proposed a service for rich people: handlers who would mess up the unread books on their shelves to make them look thoroughly perused. From this thread, the actor-writers have spun a glittering web of humor, wit and insight.

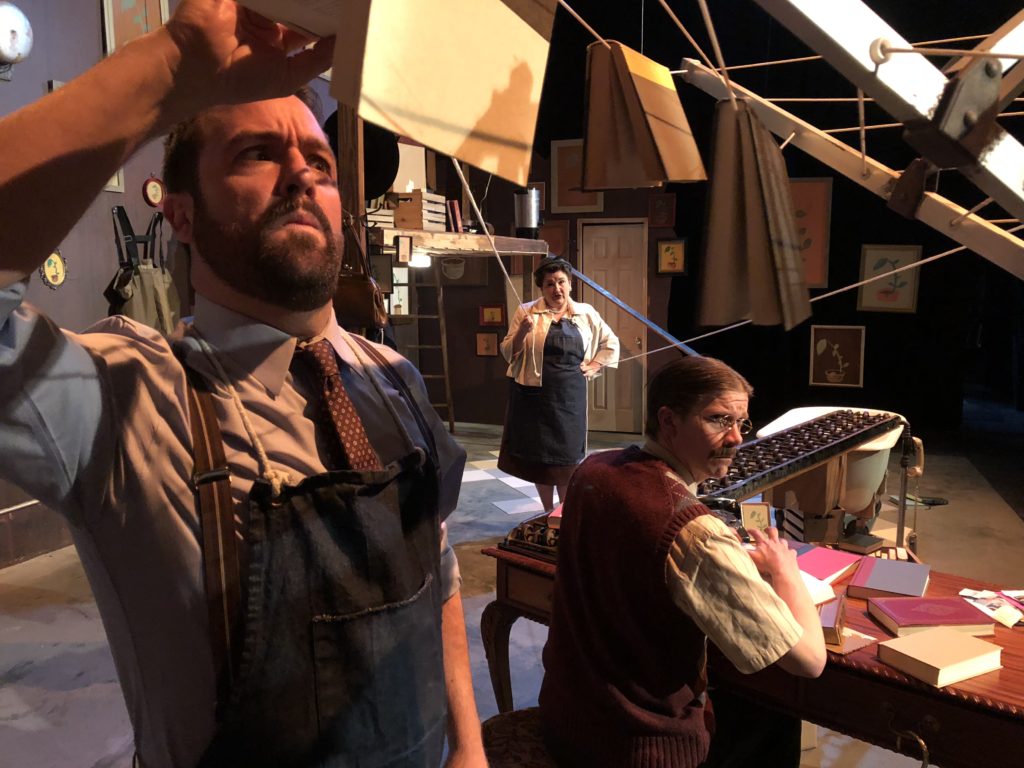

Start with the set, which looks like a life-sized Rube Goldberg contraption except for the fifty or so framed pictures — all shapes and sizes — of the same flower all over the walls. I really don’t know what these pictures signify, but I’m sure it’s something interesting, and they do keep Erin Rollman’s Linda busy painting at home and dusting at work. And who knows why the four handlers have set up this complex system of ropes, slides, platforms, racks, dangling buckets and levers to perform their work. Apparently you don’t just employ a little water to dampen a book properly, you don a clumsy wading suit and descend into a water-filled tub. Once there, you choose between complete immersion and flicking water drops onto the pages. While one of the handlers is doing this, the others are scuffing, dog-earing, scribbling notes into margins and, with much brow-furrowed effort, coming up with inscriptions. The period seems to be the 1940s to early ’50s, given Hannah Duggan’s flat little green hat and short white jacket as Connie Diane, and frequent mentions of the Andrews Sisters’ “Chattanooga Choo Choo,” though, Erik Edborg’s John looks rather Victorian. At any rate, time is fluid here, and Susan Sontag gets name-dropped before the evening is over.

The Book Handlers works on many levels. In some ways, the play itself becomes a book — maybe one of those marvelous intricate pop-up books that intrigued us as children. “Dog-ear this moment,” we’re instructed at one point. It also often becomes self-referential, with an actor addressing us directly to deliver a footnote or critique the script we’re hearing. Sometimes Duggan or Rollman will comment on her own character in the third person. Connie Diane doesn’t read much, but she proposes tackling Alfred P. Sloan’s autobiography and writing a memoir about the experience of reading it. The evening tends to evoke the idea of Russian stacked dolls and includes images within images like the intricate folds of a brain. Brian Colonna’s Jard — the only serious reader in the group — discovers O’Nolan’s essay and tells the others about it. This makes them all uneasy. Does it mean their job is satiric rather than real? Eventually, we get a swift exegesis of everything we’ve heard and seen that puts text, footnotes, phrases and key words together in a clear outline. Well, momentarily clear, because trying to recall it later, I found the outline dissolving in a silvery haze.

The primary theme has to do with information, the way we select, process and organize it, how we each individually understand the things we know. And also how apparently unrelated bits and fragments can link or cohere: Offer Rollman’s Linda a cup of tea, say the word “Darjeeling,” and brace for her lecture on colonialism. There’s reference to H.G. Wells’s concept of the world brain: a universal encyclopedia everyone could access and that would help bring about world peace through the dissemination of information. We have something very like this now, of course, but the Internet’s contribution to peace is questionable.

In the context of this play, it’s interesting to think about how the Buntporters put a work together. After seventeen years of collaboration, they must be inside each other’s minds, sorting, stealing and sharing facts and ideas. This play’s odd, unexpected, cunning, apparently irrational yet oddly meaningful set almost serves as a metaphor for the process.

This is a fizzy, heady evening — deeply clever, but not in an intimidating, hey-look-at-me sort of way, in part because the characters are real and specific and the performances so spot-on that you don’t think of them as performances at all, just people going about their business in front of you. Buntport has long been a bright spot for Denver theater-goers, and here the actors are working at the top of their form. Don’t miss it.

Juliet Wittman, March 7, 2018, Westword