Those who love Buntport Theater Company know that this group of five writer-producers tends to seize on intriguing small facts with unseemly relish and pick away at them until they’ve either disappeared altogether or dissolved into laughter. Recently, performers Erin Rollman, Brian Colonna, Erki Edborg and Hannah Duggan, along with offstage impresario SamAnTha Schmitz, discovered that mice sing. And they do: The males sing sweetly birdlike songs to court the females, though the pitch is too high for humans to hear.

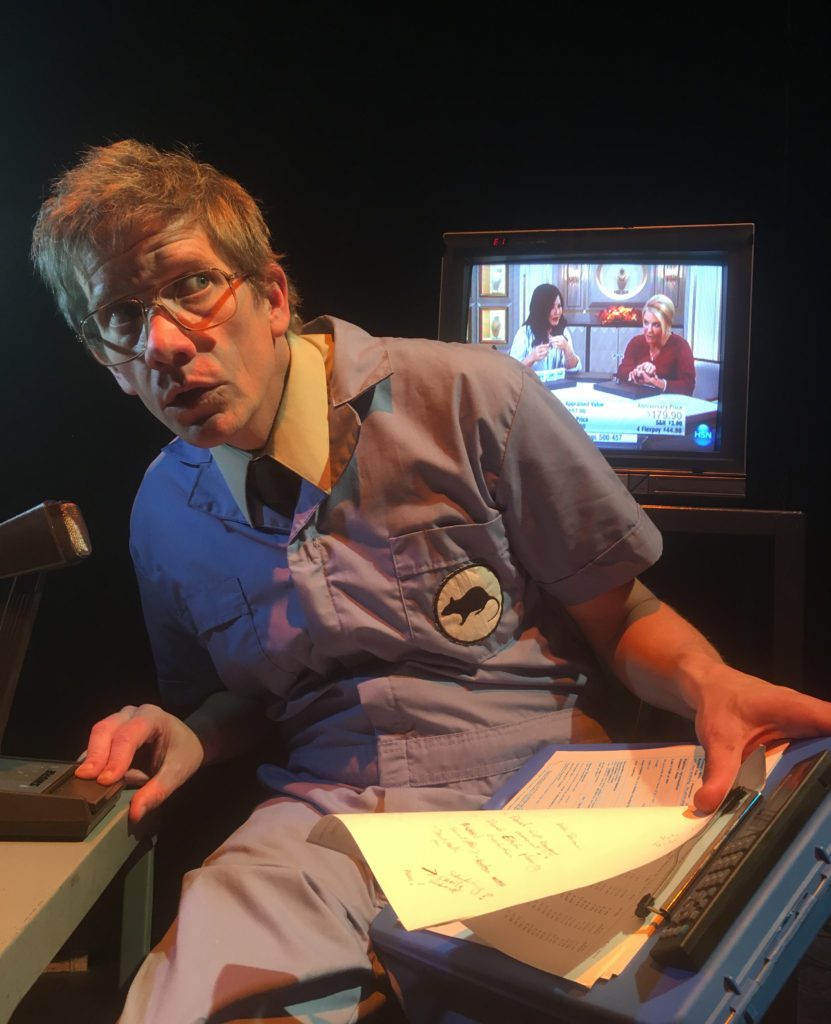

Singing mice aren’t at the core of the company’s latest offering, Universe 92, but the mysteries of animal behavior and cognition are, and there is a bit of song. The company has created a large Rat, excellently played by Colonna, who lounges in a hammock and now and then bursts — hoarsely and not at all sweetly — into outdated pop songs. Using a microphone.ADVERTISING

Colonna’s Rat is contained within walls painstakingly made of cut-out cardboard pieces. He’s a lab rat, all on his own and under study. He talks, sometimes makes a clicking-chucking sound. The three other actors are the lab assistants who take care of Rat and test him in various ways — though not in some of the ways you’d expect. They don’t open his head to insert wires into his brain or test his response to GMOs. Mostly, they give him objects and ask him to rate these with either stars or the kinds of faces you get on a pain scale. Rat isn’t very interested in their work. His ratings are tossed off contemptuously or simply not forthcoming. The objects include the microphone — which he loves — as well as a brush he uses to groom his own belly, a bunch of celery (which he rates a complete bust), a turkey knife, and an object that’s a major success, which everyone seems to see as essentially alive: the Roomba. Because if you’re examining the essentially unfathomable boundaries between animals and humans, why not contemplate the meaning of artificial intelligence in robotic objects, too?

We know the Buntporters have their own relationship with inanimate objects. If you can turn Laertes into a Teddy Ruxpin bear and Ophelia into a goldfish in Something Is Rotten, your version of Hamlet, your sense of the difference between animate and inanimate is so weird that of course you can get a roomful of people fixated on a zooming, glitching, bustling little Roomba.

While I can swallow the idea of a giant talking rat, and know that rats are commonly used in experiments because of the similarities between their brains and ours, I don’t understand why Rat is being asked his opinion on things you’d find on Amazon or Facebook ads or popping up in marketing e-mails. There’s a lot of talk about the commodification of all our tastes, wants, ideas and peccadilloes, which are monitored, stored, sold and used to assess everything from who’s most likely to vote in an election to who is searching for sandals right now. But does anyone want to know if their toothbrush would appeal to a rat?

The three researchers are very different in their approach, and — since all of the Buntporters are wonderful performers — they’re each uniquely fascinating. Dr. Lorelei MacGuire (Rollman) is all business. She wants data, data and more data, and she’s deeply opposed to empathetic human-rat interaction, which can mess up the figures. She’s not a true scientist, though, because she has no intellectual curiosity. She doesn’t care what the data actually reveal, just wants them sent to the people who slice, dice and monetize them. Pamela Hamilton (Duggan) has a bit of an inferiority complex because, unlike the other two, she has no doctorate. While she does seem to possess a certain sense of wonder, it’s not about science, and her impulsive and very funny questioning tends to annoy MacGuire and Dr. Frank Calhan, played by Erik Edborg. Calhan is the researcher with soul, a lonely, baffled man who longs to connect with Rat in some way. But if you’re hoping one of those wonderful, off-kilter relationships will develop — the kind that shows up on videos where a cat and an owl play together or creatures emerge from the depths of the sea to nuzzle a woman lying on the beach, you’re not going to get it. Rat is not only surly, but very literal-minded. Except when it comes to Roombas.

There’s lots of food for thought beneath the fizzy pleasures of this show: about science and the virtues of using observation and inference as well as straight-up numbers; the ethics of experimenting on sentient beings; the desire most of us feel to understand animals and all the myths and stories that desire generates. Perhaps central is the paradox of rats themselves, those despised, supposedly filthy creatures that, as people with pet rats will tell you, are in fact smart, interesting and affectionate.

Universe 92 might be even more interesting if Buntport had looked deeper into these things, and into what numerous studies are telling us about creatures we think we understand though they occupy entirely different sensory-psychic-neurological worlds. We now know that rats seem to laugh when they’re tickled. Even stranger, they can be taught to play hide-and-seek with scientists — not for food or to avoid electric shocks, but apparently for the sheer joy of play. A stronger examination of such intriguing facts could add significance to this intelligent and entertaining production.

Juliet Wittman September 30, 2019 Westword