I’ve already seen Buntport Theater’s Titus Andronicus: the Musical twice. But with a few honorable exceptions, theater-going has been pretty dismal this fall, so I figure I’m entitled to a little fun.

As we prepare to file in, we see an eccentrically clad woman in the lobby. She’s commenting loudly on the decor, as well as all the newspaper reviews and award plaques pasted on the walls. She does this with such conviction that it’s a few moments before I realize that she’s Buntporter Hannah Duggan, and the play has essentially begun. The conceit is that a wandering troupe of five actors, led by P.S. McGoldstien, is presenting Shakespeare’s bloody and incoherent Titus Andronicus as a musical. There’s lots of plotting here. Saturninus wants to be king, but the people are leaning toward Titus, conqueror of the Goths, who’s just returned to town with four prisoners: Goth queen Tamora and her three sons, one of whom he rapidly executes. Tamora marries Saturninus, and proceeds to plot revenge on Titus — a revenge that includes having her two surviving sons kill Saturninus’s brother, Bassianus, and rape and mutilate Titus’s daughter Lavinia, Bassianus’s love. More plot twists include the framing of Titus’s two innocent boys for murder; Tamora’s affair with the villainous Aaron, which results in an illegitimate baby; Titus’s attempt to save his sons from execution by cutting off his own hand; and a feast during which Tamora is served pies containing the flesh of her own children — that is, the sons who destroyed poor Lavinia.

Buntport actually gets us through the entire plot, and it’s all quite coherent — or at least as coherent as the original. The troupe uses a board with caricatures and lightbulbs to tell us which of the five actors is playing which of the several dozen characters at any given moment. Evan Weissman gets to act essentially the same role every time: “Someone Who Will Probably Die.” There’s also a chalkboard on which the actors keep track of the death toll. The cast makes inventive use of objects and weird scraps of costume, and not all the characters are flesh and blood. One is simply a hat on a stick, and Tamora’s sons are played by a gasoline can and a car radio, complete with ashtray. The scenery consists of a van that is pushed from place to place in the echoing warehouse space by perspiring members of the cast, while McGoldstien exhorts the audience to encourage them. This van has been painted and outfitted to represent different locations: trees on one side for a forest; a table set with plates and other dining accoutrements that pops down when needed. A stuffed owl sometimes perches on the antenna; naked umbrella spokes poke through the roof and open to reveal little green leaves; during one scene, the windows are awash in fake blood. Though I’ve seen all this before, I’m still struck by the ingenuity of the approach, and the jokes are just as funny as ever. I find myself fixing on amusing little things like the blobs of fake blood on Titus’s bare knees, or the watch on the wrist of a severed hand.

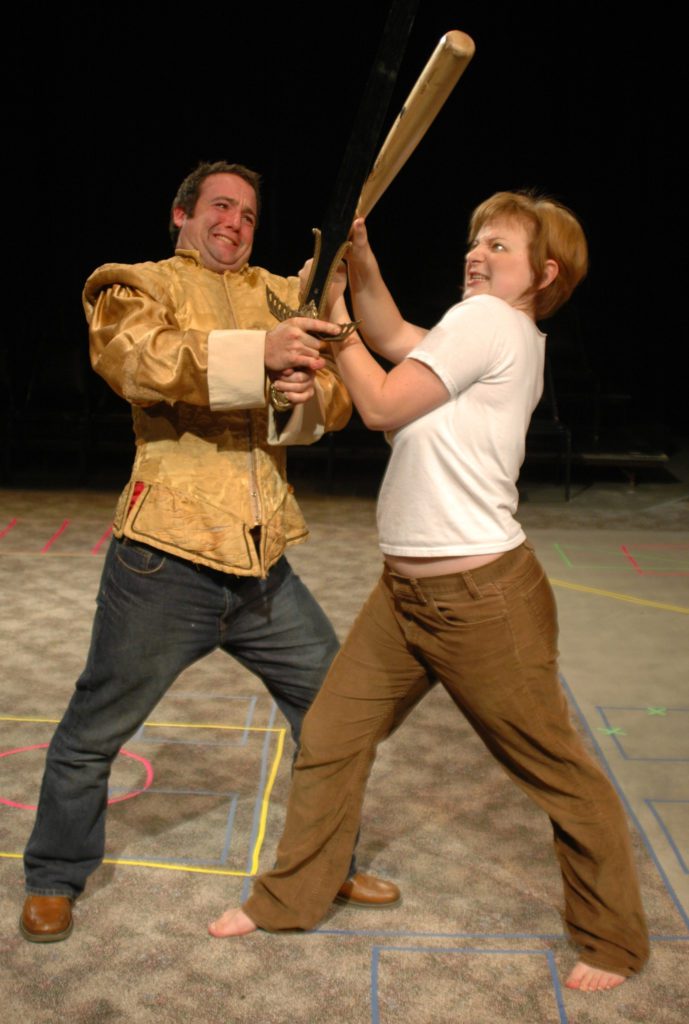

In their approach to their roles, the actors have it both ways: They speak and act with complete conviction while also communicating their awareness of the absurdity of the entire situation. They take a few pokes at Shakespeare. “It’s in the text,” one of them says after a particularly ludicrous exchange. “I didn’t make it up.” Brian Colonna is a marvel of energy and good humor as he darts from place to place keeping the entire show together; Erik Edborg manages to be simultaneously puzzled and full of insane energy; Duggan’s silent response to her mutilation at the hands of her rapists — and her tongueless exasperation when her father exhorts her to speak and tell him who they are — is priceless. Erin Rollman brings all her usual assurance to her several roles, and Evan Weissman punctures the action with a series of howlingly funny mini-characterizations.

It’s the Buntporters’ playfulness that makes coming here so pleasurable. Their work contains in abundance what so few productions have these days: exuberance and life. In this, they remind me of Al Brooks’s days at the Changing Scene: Some of the things I saw in that small, colorful space still resonate in my mind, while I couldn’t forget others fast enough. But the unevenness didn’t matter, because the entire place vibrated with energy and surprise.

There are huge differences between Buntport and the old Scene, of course. Al’s take on theater was profoundly idealistic; he believed in the art form’s ability to subvert and in its powers of redemption. He took big risks but could also be downright silly, putting on the work of almost any playwright who requested it, encouraging his dancers to cavort in the mountains naked while he filmed them. I don’t think the Buntporters are motivated by any idea of bettering society or communicating the lofty significance of art. Instead, they keep saying that their goal is to provide cheap, unpretentious entertainment — and this they certainly do.

Sometimes I wish they were more ambitious, interested in deepening and developing their work, since they are quite capable of transcendence. Instead, they seem content to alternate times of wonder and discovery with evenings that are simply amusing, but always — no matter what they’re doing — making us marvel at the good-humored fluidity of their approach and the imagination that lies at the very heart of theater.

They’re saying that this is definitely, positively, absolutely the last Titus Andronicus. I suggest you get over there.

-Juliet Wittman, December 12, 2007, Westword