We are all doomed. Isn’t that hilarious?

The six-pack of geniuses that collaborate to create Denver’s Buntport Theater have done it again with “The World is Mine,” a riveting examination of Eugene O’Neill from the inside out.

O’Neill was the most honored American playwright of the 20th century. He was also the most significant. And he’s yet another icon of the tortured-artist tradition, and by now the accumulated armchair psychoanalysis surrounding his late, “confessional” plays has permanently skewed our understanding of him and his body of work.

Buntport plays with these conceptions with adroit abandon. They set the play inside O’Neill’s mind during the germination period before his late great spate of creativity – including “Long Day’s Journey into Night,” a work so obviously patterned on O’Neill’s own family that he forbade its publication until 25 years after his death (his widow subverted his wishes, releasing it only three years after his death in 1953.)

Ostensibly, the time and place are Merritt Hospital in Oakland, California on February 17, 1937, where O’Neill received the Nobel Prize in Literature while recovering from an appendectomy (his wife took a room, too, just to keep an eye on him).

The premise is simple and freeing. We are afloat in the playwright’s consciousness, tossing chronology and logic out the same window O’Neill’s sacrificial plant falls from (you have to see it). Oh, and everyone sports O’Neill’s authoritative moustache.

Erik Edborg plays O’Neill as a paradigm of self-absorption – equal parts self-pity and self-contempt. waiting to become unstuck, paging through mystery novels, drinking steadily, and bantering with his wife Carlotta (Erin Rollman). (O’Neill’s strongest feeling of compassion is extended to the aforementioned plant.)

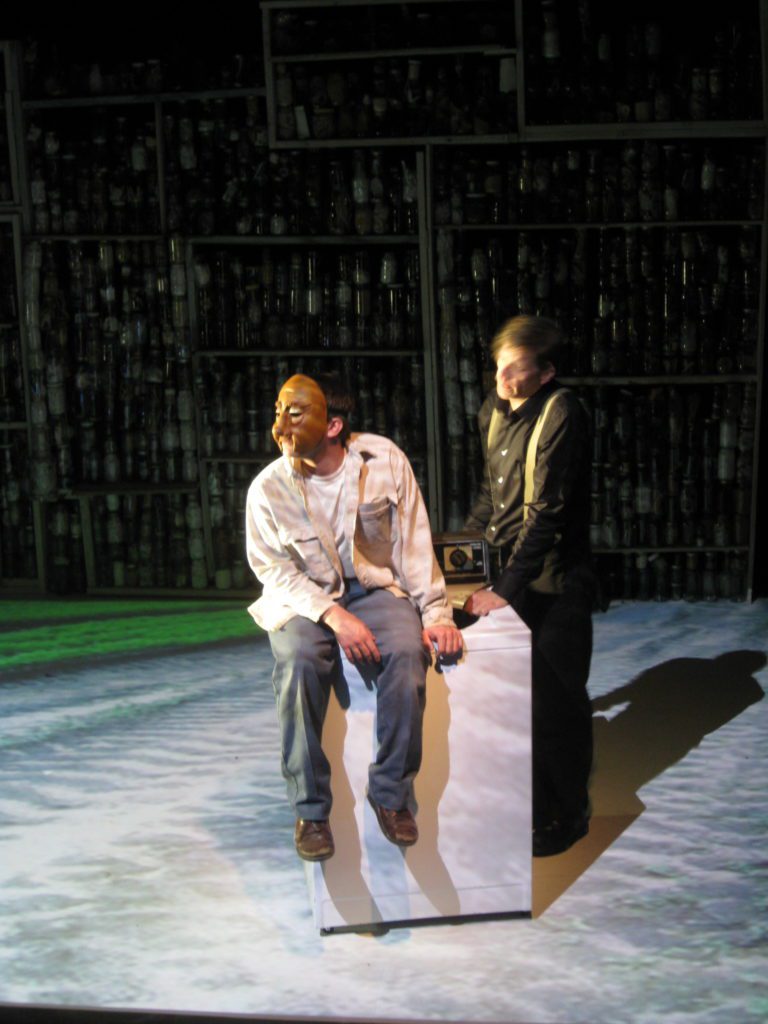

For once, Buntport presents us with a “traditional” set – almost. The room the characters inhabit looks suspiciously like the kind your average theater company would nail together to present a work of realism. The dark woody tones of the set are congruent with those found inside a writer’s mind, and the roomscape is littered with stacks of books, empty glasses, lamps and mirrors.

But there are traps, trompe l’oiel, and sight gags. Two O’Neill’s in self-portrait face each other on the back wall. As in technical rehearsals, there are tape-down marks for the furniture. The stage-right doorway is out of scale – O’Neill must duck through it. And in every object onstage lurks a hidden reservoir of “medicine” – the booze that all and sundry lap at throughout the evening, casually scooping it out of a side table, or milking a chandelier.

The “real” world is outside, and when O’Neill chooses to address that world he hits his taped X downstage center and yells into the void – at us, actually, gazing over our heads. Meanwhile, a pretty fair and funny rendition of the constant reinvention of the creative process plays out in front of us.

Trapped inside his head with him and his wife are Cathleen, a nurse (Hannah Duggan), who reminds O’Neill of his daughter Oona, whom he cut out of his life after her marriage to Charlie Chaplin in 1943 (a loop of screen test featuring Oona plays over and over on a number of screens hidden in a cupboard). Brian Colonna as Erland the Swedish emissary stomps in over and over, always at the wrong time, to present O’Neill with his Nobel.

Cathleen is also a shadow of her namesake, the maid from “Long Day’s Journey into Night,” and a female temptation, a potential nemesis for Carlotta. Colonna snaps with stupefying ease into and out of the character of O’Neill’s brother James – or is he spouting lines as Jamie from “Long Day’s”? As one point, during a tirade, O’Neill scrambles for paper and pen to transcribe the invective.

The overlying mood is that of suffocation and torment. (No wonder O’Neill loved Strindberg.) Buntport’s O’Neill can’t stop memories from intruding, replaying with variations in his head. In a closet sits his famous father’s costume from “The Count of Monte Cristo,” the hit play in which he found himself trapped, playing it over 6,000 times. When Carlotta throws it out, a replica appears in its place. “It never goes away,” Edborg intones mournfully.

Rollman’s daffy gloom seems a quite plausible way to characterize the last Mrs. O’Neill. Born Hazel Tharsig, she fled into the persona of Carlotta Monterey. She parlayed an affair with a wealthy Wall Street banker into an annuity that later helped support Eugene while he wrote his way to fame. She, chock-full of suspicion and paranoia, was determined to be the wife of a genius, and she effectively alienated him from everyone else, effectively imprisoning him so that he could work.

Her dithering with the cheesy details of the faux-Chinese mansion she intends to build with his Nobel Prize money did indeed get built as Tao House, where he scribbled out his last “confessional” masterpieces before the tremors of late-onset celebellar cortical atrophy destroyed his ability to write, and finally, move and speak. She sheltered him and herself – a haunting touch not mentioned in “The World is Mine” is that she, like O’Neill’s mother, was an addict. (She took, of all things, potassium bromide, an anticonvulsant and sedative.)

As usual, Buntport doesn’t really explicate anything. They produce a spray of ideas, associations, and fantasies and let them roam free, bouncing and colliding on stage. This removes the impulse to spoon-feed meaning to the audience, forcing it to collaborate and complete the puzzle presented.

When “Jamie” from “Long Day’s Journey into Night” is speaking, he’s not spewing a transcription of conversation brother James O’Neill, Jr. spoke decades before. In “The World is Mine,” O’Neill is doing what every creative person, haunted or not, does: rewriting, editing the past on the spot and ever after, and forcing it into position.

For better or worse, O’Neill’s family will now always be confused with the characters he created out of them. We are obsessed with the “truth,” how “real” the characters are, as if their value and validity can only stem from how closely they reveal the personal. If you’re not spilling your guts, nobody cares.

But it’s important to remember that when O’Neill won the Nobel Prize, he hadn’t yet delved into his personal past. Instead, he had created a large body of poetic, experimental work – including such great plays such as “Mourning Becomes Electra,” “The Hairy Ape,” “The Great God Brown,” “All God’s Chillun Got Wings,” his Glencairn cycle, “Ah, Wilderness!” and “Strange Interlude” – the last of which permeated public consciousness to the degree that Groucho Marx makes extended fun of it in a scene in “Animal Crackers.”

In a 1924 New York Times piece about Walter Huston, who was busy originating the role of Ephraim Cabot in “Desire Under the Elms,” John Corbin wrote of the performer’s task in O’Neill: “The actor has so much actualistic matter on his hands that he must be convincing as realism, but at the same time he must evolve a creation that transcends realism or resemblance.”

This Buntport gets, and like any great theater group it doesn’t tell us, it shows us. Its slim anchor line to “truth” leads into a more fantastic and truer realm.

O’Neill’s brand of drunken, grueling dramatic self-examination has cast him in legendary terms. But expiation is not art – in that case, every tortured and overwrought diary would be a masterpiece. O’Neill could write his last works because of his skill, not because of his past. And if he did redeem himself by writing these final plays, ease his fevered conscience? Or did he revenge himself on the past?

Does it matter a damn?

At the last beat of “The World is Mine,” the back walls fly apart and a platform holding a pair of hospital beds is revealed. There are Eugene and Carlotta, lying side by side. He has broken through. He will write. They seem pleased. They seem happy.

-Brad Weismann, February 19, 2010, bradweismann.blogspot.com