The 30th of Baydak is a small, sweet, gentle play about a large, ragged and ugly topic: dictatorship. And since this is a Buntport production, bringing back a show it originally presented in 2003 as part of the company’s ten-year retrospective, naturally it tackles a particular kind of dictatorship. When Niyazov became president for life in Turkmenistan after the fall of the Soviet Union, he turned out to be as dotty as he was terrifying. He filled the country with huge, ludicrous statues of himself, banned gold teeth and suggested that his subjects chew on bones to strengthen their natural choppers, changed the names of planets to honor himself and his mother, and also remade the calendar. January became Turkmenbashi (Niyazov’s honorary title); Baydak was February – which can only have a 30th in the kind of topsy-turvy universe depicted here. (Niyazov died in 2006; it’s unclear how much, if at all, his successor, Berdimuhamedow, has liberalized things – a question of some interest to the United States because of Turkmenistan’s plentiful gas and oil reserves.)

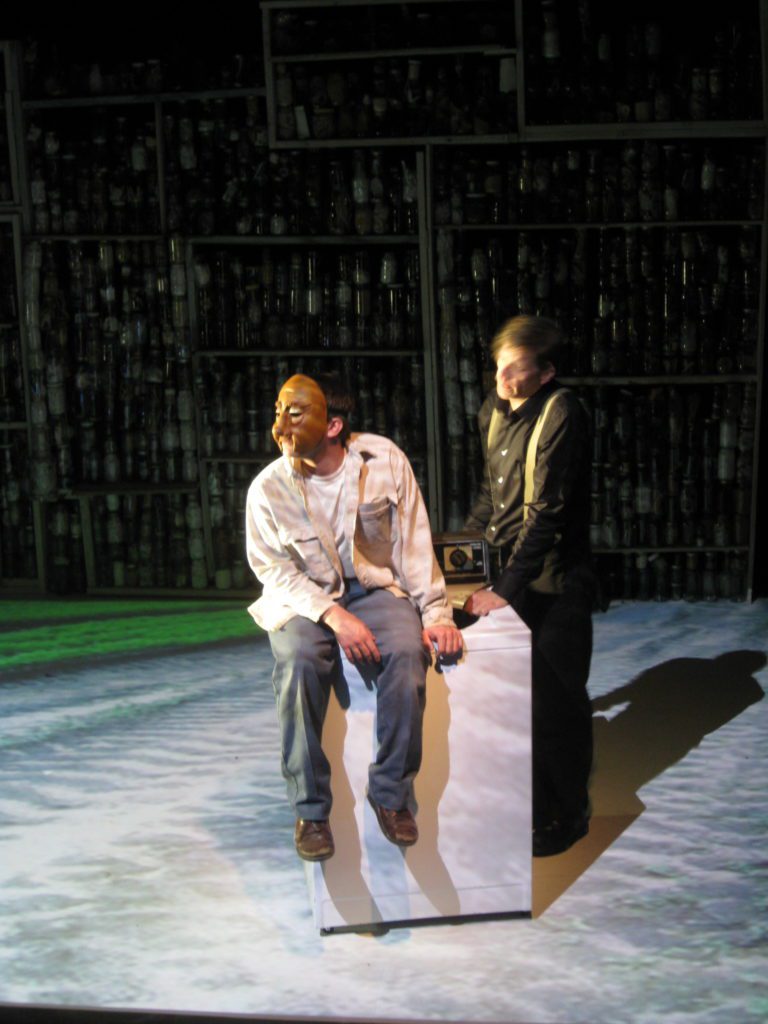

The action stays away from anything large or lurid. What we see is an office drone named Yousef, quietly excising the now-forbidden former month names from official documents. A huge photograph of the dictator graces one wall (what is it with ruthless dictators and jet-black hair?); smaller photographs of him are visible elsewhere. A bustling woman brings Yousef an armload of papers and spouts cheery clichés; a co-worker arrives late, gesturing his defiance as he passes the portrait – and this entire sequence of events repeats, as if Yousef’s life is some kind of Groundhog Day. Then one morning a young woman, Meret, arrives to occupy the cubicle next to his. She places a small plant carefully on her desk. She and Yousef can’t see each other, but they regularly pass papers through a slot in the wall, and pretty soon they’ve wordlessly fallen in love. But then the regime tightens its grip.

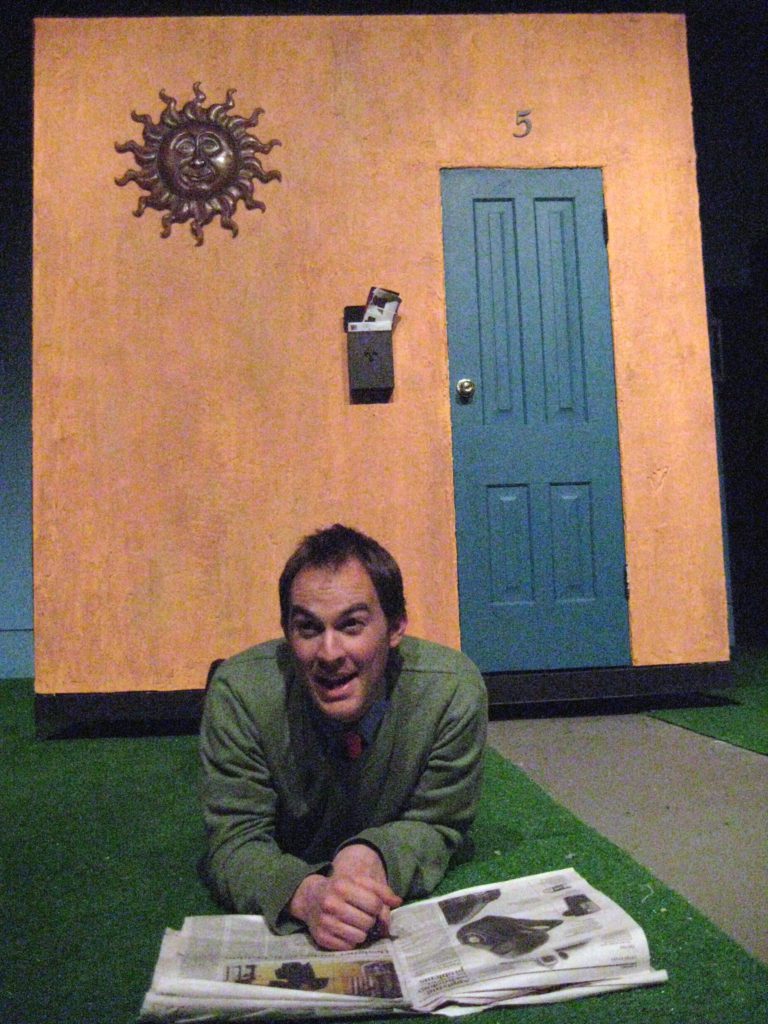

This is territory we know from George Orwell’s 1984, where the protagonist spends his days at the Ministry of Truth, sending all photographs and documents that contradict the government’s frequently changing official version of events down a chute called the Memory Hole and into flames. How do you survive in a place where your life and work are meaningless, where history can be changed or obliterated at the will of the powerful? You keep your head down, allow yourself small but meaningful acts of defiance, try to maintain a sense of the absurd, look to art or love to free your soul. And if you’re imaginative, you escape into magic. Yousef – who spends his evenings conversing with an affable camel and who undertakes a portrait of Meret made up of torn-out months – tries all of these.

The small, telling gesture with which The 30th of Baydak concludes is a little disappointing. Obviously, a hyper-dramatic ending wouldn’t work, but if this world can’t end with a bang, you’d like at least a deeply resonant whimper. Still, the production’s significance doesn’t really lie in the script or a lot of overt action, but in image and metaphor. The title is telling: When you’re confused about your situation in time, you’re lost; nothing coheres, and there’s no ground under your feet. So it makes sense that most of the set is actually suspended rather high above the usual acting space by wires, and that the catwalks leading across the theater to the office cubicles sway under the feet of the actors. The rhythms are telling, and also unhurried – no one here is afraid of pauses – and small objects like Meret’s living plant carry a great deal of meaning. There’s also a surprising and absolutely beautiful moment when Yousef shows his artwork to the camel.

The performances of Erin Rollman as Meret and Eric Edborg as Yousef are one of this production’s most impressive aspects. Almost any actor can command a stage when he’s called on to yell, kiss, grieve loudly or fight, but it takes deep skill to hold audiences rapt while actually saying and doing very little. We know everything we need to know about Meret’s character – her gentleness and generosity, the kind of stubborn, low-key courage she possesses – through Rollman’s economical gestures: her calm smile, the way she arranges her legs just so under the desk. Edborg’s Yousef is more loquacious, but his performance is equally restrained: no raging or kicking against the pricks, just small moments of hope, resignation or despair that lie quietly in your mind for some time after.

-Juliet Wittman, April 12th, 2011, Westword