One of the things I love about Buntport is how the company comes at a subject from a genuinely original, sideways angle. Dramas based on Alexandre Dumas’s The Three Musketeers are usually romantic swashbucklers. But the Buntporters, who create their scripts through a collaborative process, were more intrigued by news stories from a few years back that told the kitschy yet oddly touching tale of Dumas’s body being exhumed and transported from the cemetery of his native village, Villers-Cotterêts, to Paris for burial at the Pantheon. The coffin was accompanied by actors dressed as Dumas’s characters and greeted in Paris by a white-robed woman on horseback representing Marianne, the spirit of France. President Jacques Chirac then read a solemn tribute to the author, who some critics considered too popular to be truly literary. And for this production, the troupe also fixed on a second fact, which they admit they found in Wikipedia: Dumas based his famous novel on a book he’d checked out of the Marseilles Public Library and never returned.

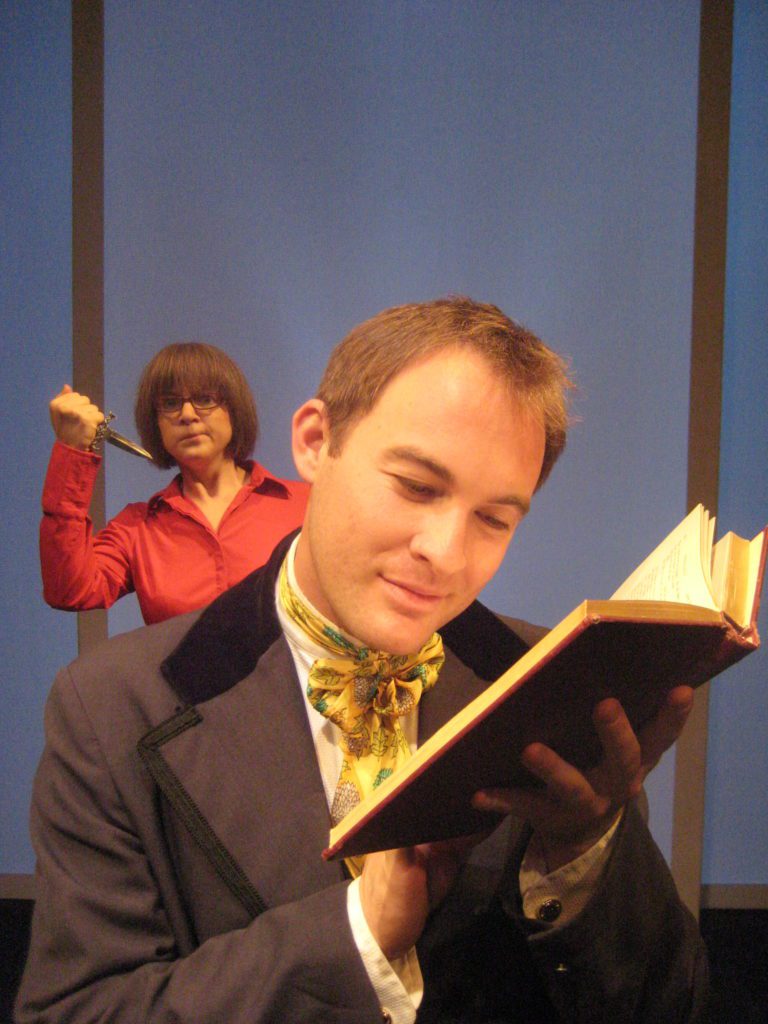

From this juxtaposition, we get a contemporary librarian named Charlotte (like all librarians who aren’t named Marian), who has noted the overdue book and is determined to get it back from Mr. Dumas — a feat that involves waylaying the coffin, confronting the three faux musketeers escorting it, and eventually engaging in a very lively duel of wits with the deceased author himself. In the course of all this, Charlotte is transported back in time to the carriage ride during which Dumas first read his library book, pondered its shortcomings and began to conceive of his own deathless characters. These scenes, in which the author transmutes tendentious dross into fictive gold while arguing with Charlotte about the virtues of logic and order versus those of romance and invention, are among the most delightful of an altogether delightful evening.

As regulars know (the company is starting its eighth season), Buntport achieves its effects in large part with low-budget but highly ingenious staging. A large wooden box serves as both Dumas’s coffin and his carriage. Borrowing the technique from former college classmate Thaddeus Phillips, Buntport also makes brilliant use of video — and the borrowing is particularly appropriate, since Musketeer explores issues of originality and the debt all artists owe their peers and predecessors. Three large screens in the center of the playing area show us the shelves of Charlotte’s library; placid green scenery moving past Dumas’s carriage; Charlotte and Dumas squished together inside the coffin, arguing. Many of the onscreen images are very beautiful: tall, waving grasses, radiant skies. Through a trick of light and perspective, characters leave the playing area, cross behind the screens and seem to enter a magic zone, becoming elegant silhouettes.

There are terrific bits of dialogue as well, as when the three people walking the coffin to Paris discuss their lives and why they’ve taken on this job. Gilbert tells the others he plays Porthos for children’s birthday parties, where he duels with balloon animals. Simone wants to go to cooking school, and comes up with a wistful description of the process of making fish quenelles. (Dumas himself was a well-known gourmet.) And Edgard was once in love with Charlotte and isn’t yet over it.

All of the actors — Hannah Duggan, Erik Edborg, Brian Colonna, Erin Rollman and Evan Weissman — are versatile, funny and expressive. Weissman makes Dumas preternaturally good-natured and unflappable, while Rollman brings schoolmarmish precision to the role of Charlotte. And Andrew Horwitz’s music adds zing to the event.

Despite the production’s many strengths, the plot isn’t entirely satisfying. There’s a jolting contrivance toward the end. And although Charlotte’s onetime affair is intriguing, it never becomes a significant part of the story, and neither she nor Edgard changes or develops as a character. Still, Musketeer is enjoyably nutty and farcical, with duels erupting at the drop of a hat, slapstick humor and absurd running jokes. And there are serious ideas here as well: questions about the artistic process (one of Dumas’s own characters asks him to slow down and put more thought into the writing), as well as a growing understanding that poor Charlotte may be the guardian of these texts, but she can never understand the life throbbing inside them, a life that continues to enthrall readers more than a century after their creation. Watching this daring, imaginative work, we’re reminded that the process of transmutation from fact to fiction and fiction to art is one that the Buntporters explore every working day of their lives.

-Juliet Wittman, August 14, 2008, Westword