Oh ye citizens of area metropoles, it is time to get your Greek on. And two creatively robust theater companies are here to help.

The Boulder Ensemble Theatre Company and Denver’s Buntport have torn down the fourth wall to engage audiences with a tale of humans and gods. One utilizes the poetics of disaster and melancholy. The other plies mirth and throws one hell of an unreal supper party. Each boasts the fine services of a local acting luminary.

That Boulder’s “An Iliad” has timeless lessons is not exactly edifying news. Lisa Peterson and Denis O’Hare’s terse adaptation of Homer’s epic wrestles with the human tendency toward endless — and, in the case of the Greek-Trojan conflict — vain warfare.

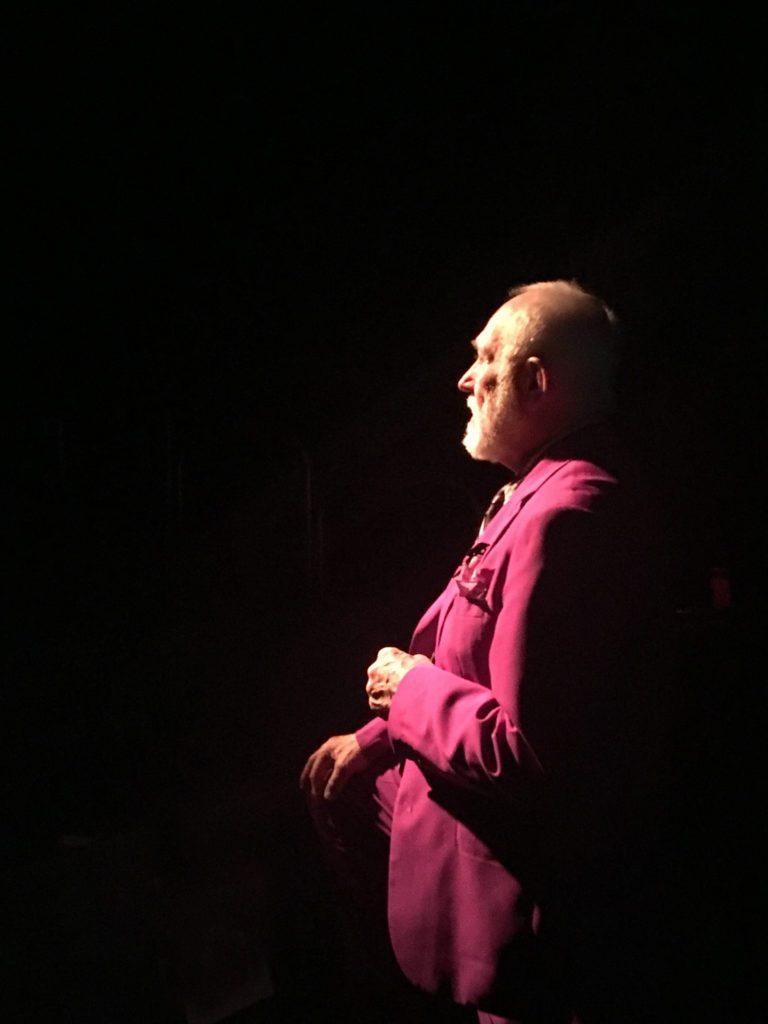

Yet there’s great news to be had in the production, directed by Stephen Weitz. Chris Kendall’s performance as The Poet in this one-man show is awe-provoking.

The Poet arrives to the set carrying a rucksack of clinking bottles, tequila and whiskey. Sometimes he can be fuzzy on the names of the warriors — and the wars. Then again, his account isn’t limited to the bloody goings-on in Troy. At one point, a misremembered battle leads him to a foggy litany of wars. “The Punic War … The Fall of Rome …The War of the Roses … The Pequot War … The Mormon War … The Six Day War … The Troubles … Vietnam … Syria” all get a shout-out. (Ron Mueller’s set hints at the ruins of recently bombed-out towns as well as ancient dusty plains.) It is a feat and a burden to recount so much blood-letting, so much loss, so much hubris. Of course, he self-medicates.

The Poet’s recitation delivers the big names. There’s Achilles and Hector, Agamemnon and Paris. But he also sings of “the fighters of Coronea,” who man the ships in the bay outside Troy. “An Iliad” puts contemporary audiences in uncomfortable company. Such was the playwrights’ purpose in 2012, when the play premiered at the New York Theatre Workshop. (It won an Obie.)

When his memory slips, it bolsters the lessons of the play. “The point is,” The Poet continues, “on all these ships were boys from every small town in Ohio, from farmlands, from fishing villages.”

With graying hair and grizzled beard and eyes searingly focused on distant but riling memories, Kendall grabs hold of The Poet’s epic lament and never lets go. This is a performance of pause and vigor, hush and heat, not be missed but to be thrilled and chastened by.

*****

A different myth is getting a witty once-over in Buntport’s original one-act play, “The Zeus Problem.” What a dandy, a strutter, a bully Zeus is. What relish Jim Hunt takes in embodying that trespassing, traipsing, charismatic god.

A table — a really long one — is set for an odd, bickering dinner party. On one end sits Henry David Thoreau (Brian Colonna), hunched over a manuscript. He’s adapting “Prometheus Bound.” On the other end, Prometheus (Erik Edborg), Eagle (Hannah Duggan) and Io (Erin Rollman) huddle together. Zeus, being Zeus, takes any position he pleases.

How did this collection of guests come to be? Well, getting at that is the pleasing task of this comedy. Zeus has some very different ideas about Prometheus’ never-ending end. You may recall that the Titan’s punishment for giving humans fire found him chained to a rock, an eagle feasting on his liver. Duggan’s cranky Eagle would peck hard at the notion of “feasting.” Also up for debate: How did Io, the mortal daughter of Inachus, come to be a cow? Was it Zeus hiding her from his wife, Hera, or Hera herself? Or was there some other, darker cause?

The delightfully weird animal costumes for Io and the Eagle are themselves worth a night out. And the two characters chime in with critiques — smart and silly — on the sexual politics of the whole enterprise, often rendering “The Zeus Problem” utterly playful and pointed.

Did I mention the table is long? It’s long enough to become a runaway when Zeus feels the urge to vamp, to vogue, to shake his groove thang and pantomime the hurling of lightning bolts.

“An Iliad” and “The Zeus Problem” encourage us to slip into joy and sorrow, hilarity and ache. They represent a fine kind of escapism. One dons the mask of tragedy, the other comedy. And when those masks slide away, it is ourselves that we see.

Lisa Kennedy, February 16, 2017 Denver Post