Take some Shakespeare. Turn it upside down, inside out, slap it around, shake it like an unopened can of paint, hang it on the wall and make fun of its mamma.

That’s the approach Buntport Theater takes to what it calls “the Bard’s bloodiest play,” “Titus Andronicus.” What results is a crass, sardonic, no-holds-barred gorefest (stuffed with toe-tapping musical numbers) that is one of the funniest experiences you are likely to have on what the evening’s host refers to as “a flight on that big bird called theatre – with an R, E, of course.”

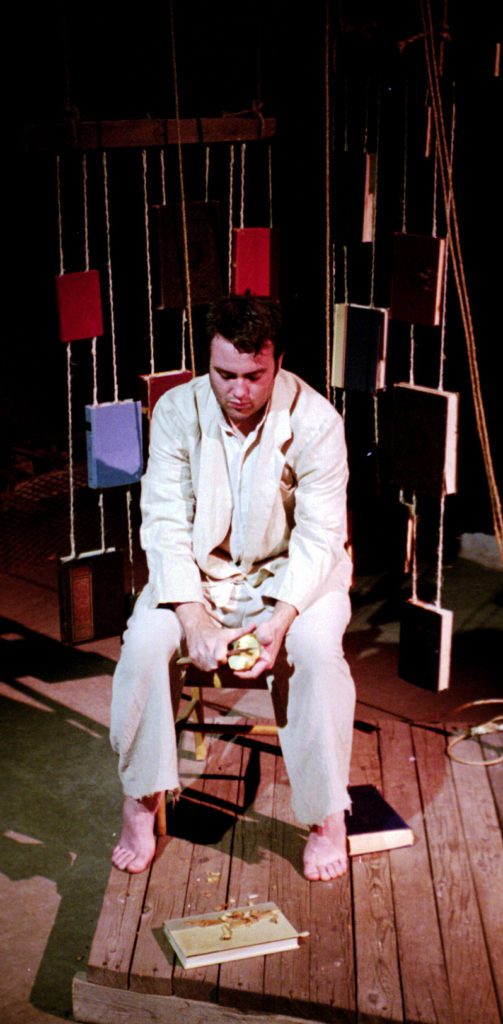

The show takes place in Buntport’s bare-walled performance space, occupied only by a massive Club Wagon XLT van which serves as the surprisingly versatile set, a player piano and tape deck, and a light-bulb-studded tote board, the last of which helps us keep track of who’s playing whom in each scene. A drop-dead-funny cast of five, who present themselves as the traveling “Professor P.S. McGoldstien Van-O-Players,” portray the near-infinitude of characters in “Titus.” They aid their cause with the help of a stripped-down text crammed with cheesy gags, clever no-budget costumes and props, and a flock of quick-change costume pieces that help to keep the players straight – barely.

A summary of the play’s gruesome and complex plot, thought to be Shakespeare’s first effort at tragedy, would eat up too much space. Besides, Buntport’s hilarious program captures its absurdities nicely. Its mélange of high-flown eloquence, revenge, murder, rape, insanity, dismemberment, and cannibalism has rendered it unproduceable by all but the hardiest and most grimly insightful of directors. Of course, this makes it perfect fodder for parody.

Each performer takes on a handful of roles with relish – and a great deal of ketchup, which is splattered about profusely as the bloodshed swells (updated as expirations progress on a handy “Death Toll” chalkboard). Brian Colonna, a bundle of energy despite undergoing an emergency appendectomy only days before the opening, sets the tone with joyful, manic bombast as Titus, and with wimpy delicacy as the hapless suitor Bassanius. Erik Edborg scores as a wheezy emperor, Titus’ wistfully dense would-be-hero son Lucius, and as the voices and hands powering the evil brothers Chiron and Demetrius, who are puppets incarnated from a car radio and a gas can, respectively.

Droll Erin Rollman handles her manifold acting duties with style and wit, especially as Titus’s befuddled brother Marcus, and as Titus’s nemesis, the Goth queen Tamora. Hannah Duggan is brilliantly funny, doubling as the evil Aaron the Moor, complete with Snidely Whiplash moustache, and as Titus’s doomed daughter Lavinia, who, lopped of tongue and hands, she still gamely serves as a mute and melancholy Ann Miller. Tasteless? Sure. Funny? You bet.

A new and welcome Buntport participant is gangly Muni Kulasinghe, who runs the musical portion of the show and fills in as any number of incidental characters whose demise is imminent. His profusion of idiotic impersonations adds immeasurably to the show’s bounty of belly laughs. Classical music lovers will find his baleful plucking of the “Dies Irae” on mandolin a howl. Kudos also to the troupe’s often-overlooked backstage members, Matt Petraglia and SamAnTha Schmitz, who keep the comic havoc flowing.

“Titus” gleefully mocks the Bard and all who have made him into the playhouse’s sacred beast. In an area where “serious,” big-budget productions draw crowds and media attention, Buntport proves that entertaining theater (or theatre) can be composed of nothing more than a minimum of stage effects, a powerful collection of talent, and an abundance of imagination. “Titus – The Musical” deserves packed houses for the remainder of its run.

-Brad Weismann, May 14, 2002, Colorado Daily