Buntport Theater has fun with one-acts and paper props

Now that Buntport Theater has come of age and is attracting reliably positive reviews and large, enthusiastic audiences, the six company members have revived one of their earlier works, an evening of one-acts titled 2 in 1. The first piece, “This is My Significant Bother,” is a dramatization of nine stories by James Thurber; the second is an explication of the Cliffs Notes explication of Beowulf (it makes sense when you see it — sort of). These are both slight pieces, but they’re clever and entertaining, and the sets and costumes are as inventive as ever. It’s pretty much impossible not to have a good time at Buntport.

As the evening begins, four actors — Brian Colonna, Erik Edborg, Hannah Duggan and Erin Rollman — are lying on a large bed, their left arms in perfect alignment on the coverlet, their hands conspicuously wedding-ringed. They manage to stay absolutely still as the audience arrives and settles in. Perhaps they’re asleep. One of the evening’s pleasures is the way the actors manage to move swiftly and soundlessly during blackouts, so that we’re always slightly surprised at where they’re each standing or sitting when the lights come on.

Although he apparently labored over their composition, Thurber’s stories are sketches rather than fully developed character studies or descriptions of events. They have the wistful, unfinished quality of his New Yorker cartoons, along with a misogyny so self-deprecating that it almost seems forgivable. If his women are all-powerful, soulless harridans, well, his men are pretty silly, too, and sometimes downright irritating. (Although, in a fable Buntport doesn’t attempt, it’s only the male of the species who’s capable of seeing a unicorn in the back garden.)

“Significant Bother” is not intended to be laugh-out-loud funny. It’s a sincere and gently humorous homage to Thurber.

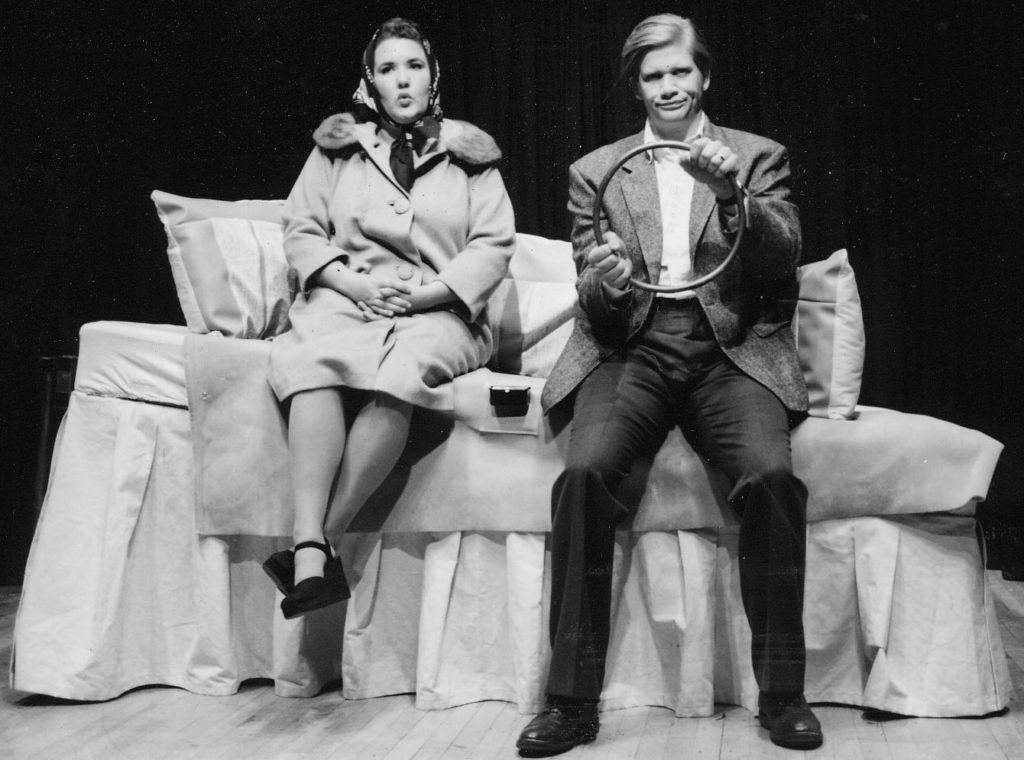

A husband manfully protects his wife from a spider but cowers under the bedclothes when he hears a bat. A woman stands up in court and insists she deserves a divorce because of her husband’s habit of holding his breath. In one of the most absurd and amusing pieces, a police officer finds a woman seated in a car while a man crawls on the ground in front of the vehicle; they are trying to ascertain whether a human being’s eyes will glow in the headlights as a cat’s or dog’s would. In another car scene, this time inside the car, a couple fights over whether Greta Garbo is a more important cultural icon than Donald Duck and bickers about where to stop for a hamburger, the wife insisting that the eatery must be a cute one. Meanwhile, the car is emitting a threatening and unidentifiable noise. Yet another husband orders his wife into the basement so that he can kill her and make off with his stenographer. Wise to his plan, she gives him orders on how to accomplish the deed. All of this is interspersed with interesting renditions of such ’30s songs as “Makin’ Whoopee” and “Happy Days Are Here Again.” And the bed that anchors the play (in the very last scene, a man painstakingly smooths the sheets while his ex-wife discusses his failings with his wife-to-be) is manipulated by the Buntporters with their usual sangfroid, becoming by turns a car, a platform, even a cellar.

Perhaps the most interesting and unexpected piece is a mood story about a doomed love affair called “Evening’s at Seven,” which is told through a series of lighted tableaux separated by patches of darkness. It’s touching, original and sophisticated.

For the second play, the cast appears in front of a backdrop of text wearing dark-blue maintenance men’s outfits and tool belts that hold an arsenal of paper props. They proceed to act out the story of Beowulf, interspersing the action with textual commentary — and their own acerbic comments. In case you’ve forgotten, this Old English poem concerns the predations of a monster, the monster’s dam (or, as the Buntporters have it, “dam mother”) and a dragon. As always, the props are inventive; in this instance, they’re made entirely of paper. Beowulf’s army consists of a string of paper cutouts worn across Edborg’s chest like a bandolier; streams of paper representing blood from a wound are helpfully and multiply labeled “blood,” just as the paper crown bears the legend “crown.” The paper dragon is a thing of wonder. Periodically, we hear a voice reading from Beowulf itself and — though you’d need to know Old English to understand the words — the power and beauty of the text makes itself felt through all the loony shenanigans.

The acting is terrific, as always, though it concerns me a little that both Colonna and Edborg act so much from the neck upward. I’d like to see their voices and impulses coming from deeper in the body. In addition to the cast, Matt Petraglia, SamAnTha Schmitz and Evan Weissman helped create 2 in 1.

I’m getting tired of saying this, but if you haven’t attended a show at Buntport yet, you should. You won’t see anything like it anywhere else.

-Juliet Wittman, May 6, 2004, Westword