Even when Buntport repeats itself, it’s the most original theater company in town.

“Kafka on Ice,” first staged in 2004, takes the standard device of a stage biography – and a mighty depressing one at that – and presents it with artistry, intelligence and a wonderful kind of whimsy.

Buntport and Kafka go oddly well together – they’re both known for different kinds of metamorphoses. Kafka is the dour Czech master of despair who in 1912 famously turned a human drone into a big old bedbug – and no one even noticed the difference.

And Buntport, which last week won a 2010 Mayor’s Award for Excellence in the Arts, routinely transforms simple objects on a stage in ways that have us watching along like slack-jawed children taking in our first Ice Capades.

The ice has something to do with that. The synthetic ice, that is, that’s been laid down on Buntport’s warehouse floor. Guest artist Josh Hartwell, playing Kafka, is the only actor who does not wear figure skates. Instead he slips, slides and struggles to find his balance while the expert Buntport ensemble, playing all the important people in Kafka’s life, gracefully camel-spin and salchow all around him. A gimmick, to be sure. An absurd juxtaposition. But for a valid creative purpose.

The play opens with a young Kafka writing at his desk, an enhanced audio effect making his scribbling motion sound not unlike a bug scurrying from light.

Soon the figure-skating five dart to and fro at speeds that suggest Kafka is not living in the same rhythm and time as those around him. There’s Hannah Duggan as Kafka’s determined grandfather, schussing across the ice with a burlap sack in his teeth (just to show how tough he was!). Evan Weissman as a parasitic Kafka mentee who would later recycle their talks into a mangled libertarian dogma – for his own (capitalistic) profit. Later, Weissman again as a maid performing a curiously elegant (and risque!) Olympics-style skating routine.

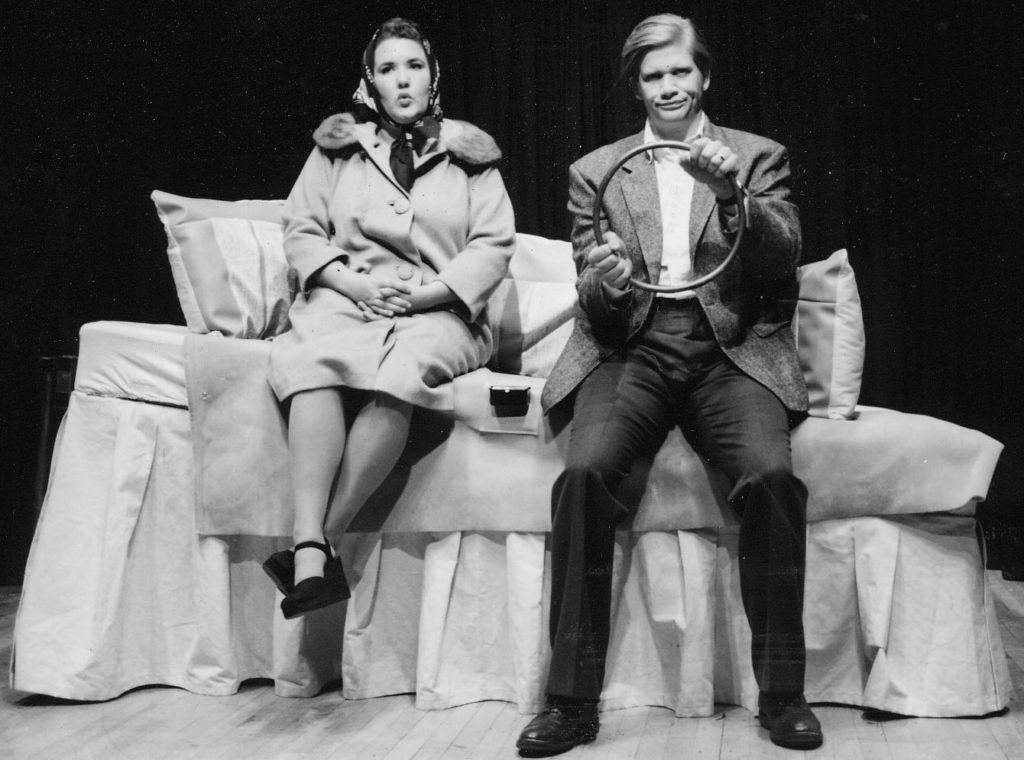

As a doe-eyed Kafka, Hartwell’s portrayal is more Chaplin’s sad clown than an embodiment of the real Kafka. That’s by design, in keeping with a presentational style that figure-eights from vaudeville to slapstick to WWF (there’s an interspecies wrestling match that, well, you’ll just have to see). Hartwell has come to be Denver’s go-to Kafka, having played him in the LIDA Project experimental theater company’s considerably more paranoid and political “Joseph K” in 2009.

“Kafka on Ice” is more personal. It focuses on the writer’s many foiled, failed relationships – from his disapproving parents to the women he kept at a distance, to the opportunistic managers who profited from his words (such as Brian Colonna as best friend and leech Max Brod).

The story plays out with a stream-of-consciousness, dreamlike quality not unlike Kafka’s own works, which blurred the line between the real and the surreal. Comic snippets of “The Metamorphosis” are interspersed, further fogging the line between Kafka and his iconic human vermin, Gregor Samsa.

It’s ridiculous and lovely, while still elucidating the sad and melancholy story of an isolated writer who, ironically, lived one of the world’s most examined and misunderstood lives.

More than that, this musically infused play gleefully, but never too pointedly, raises questions that have been bandied for a century – and gently mocks them. The most absurd: Erik Edborg, as “Lolita” novelist Vladimir Nabokov, debating whether the insect in “The Metamorphosis” is in fact a beetle or a cockroach. As if that matters.

Later, Kafka finds himself sitting in a modern-day American college English class led by an overmatched teacher (a perfect Erin Rollman) hilariously bluffing her way through Kafka’s text with the help of an online lesson plan – and a cheat sheet.

In 2004, I called this scene tangential. But I’ve come to see it as the signature moment in the play. Because the lasting questions from “Kafka on Ice” are really those that tease the fabrications, exaggerations and ridiculous misinterpretations that have followed famous people into the afterlife since the Stone Age. It’s possible, Kafka might say of all this, that a bug is just a bug. In fact, that’s the point.

-John Moore, February 3, 2011, Denver Post