THURBER’S RELATIONSHIP STORIES

A period show based on nine short stories by the marvelous James Thurber.

(more…)

THURBER’S RELATIONSHIP STORIES

A period show based on nine short stories by the marvelous James Thurber.

(more…)

An audience favorite from the early days of Buntport, based on nine short stories by the marvelous James Thurber. Featuring live music by The Hoagies.

Special event ticket $25 (reception included)

An audience favorite from the early days of Buntport, based on nine short stories by the marvelous James Thurber. Featuring live music by The Hoagies.

Special event ticket $25 (reception included)

THIS SHOW IS SOLD OUT!

We will have a wait-list (starting at 7:30) that you can sign-up for in person. Seats might become available close to show time.

An audience favorite from the early days of Buntport, based on nine short stories by the marvelous James Thurber. Featuring live music by The Hoagies.

Special event ticket $25 (reception included)

THIS SHOW IS SOLD OUT!

We will have a wait-list (starting at 7:30) that you can sign-up for in person. Seats might become available close to show time.

THURBER’S RELATIONSHIP STORIES

A period show based on nine short stories by the marvelous James Thurber. (more…)

Now that the Buntport Theater Company is winding up its tenth season – filled with remounts of several past shows – it’s time to stop thinking of this troupe as talented kids who got together at Colorado College to create a theater style all their own, and instead consider them the creators of a distinct body of work. Still, it’s hard to generalize from the year’s mix of staged readings, extemporaneous evenings and full productions culminating in the current offering of two early one-acts which – as the program helpfully points out – have nothing to do with each other: And This Is My Significant Bother (2000), a series of scenes based on James Thurber’s short stories, and an insane, babbling interpretation of Cinderella (2003). You can pinpoint specific Buntport tendencies: clever work with objects; playfulness and humor; an inventive approach that continually constructs and deconstructs the very idea of theater itself; a love of language that means the Buntporters’ favorite writers, from Melville to Kafka, are treated with a wonderful mix of cheeky overfamiliarity and profound respect. This company likes dramatizing odd fragments of fact they come across: for instance, the trauma suffered by the poor brontosaurus after it was demoted and renamed by scientists (The Mythical Brontosaurus); the obsession of one Wilson Bentley, who spent his life photographing snowflakes (Winter in Graupel Bay); the actions of Niyazov, dictator of Turkmenistan, who upended all notions of truth and time in his country, in part by renaming the months of the year for himself (The 30th of Baydak).

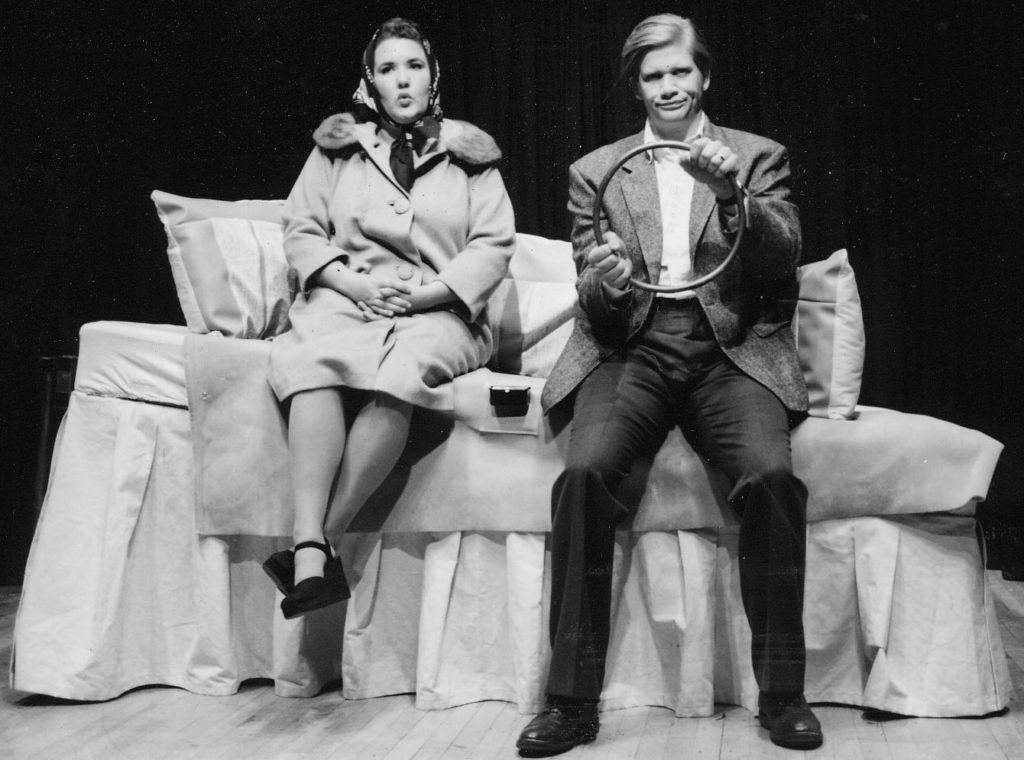

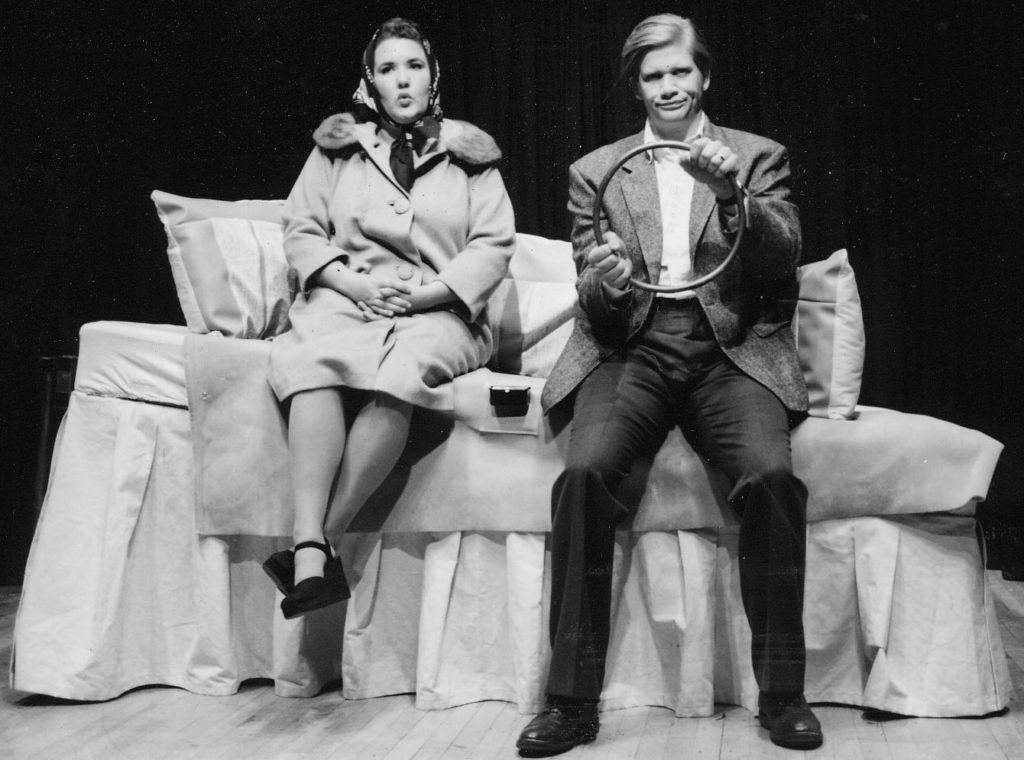

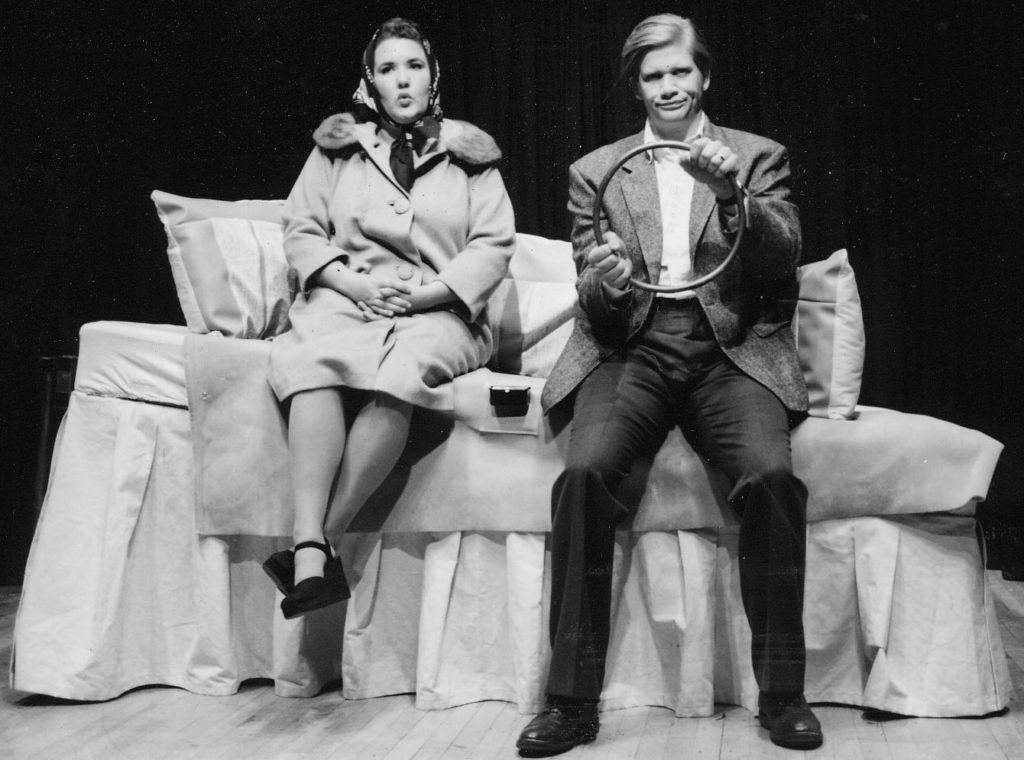

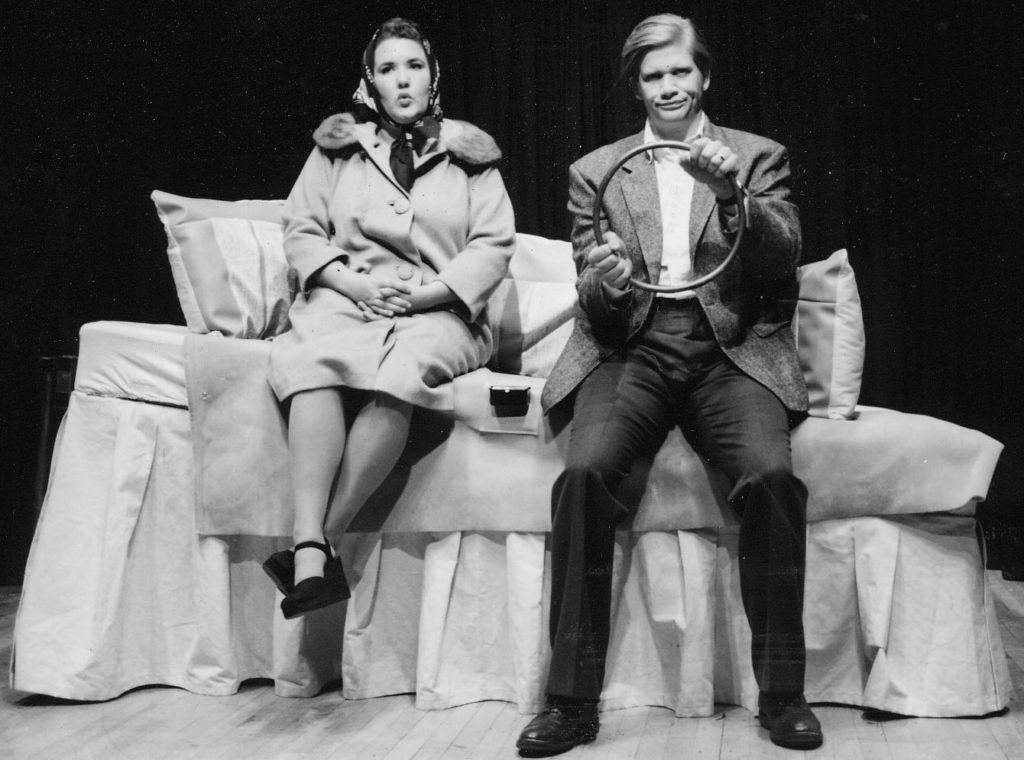

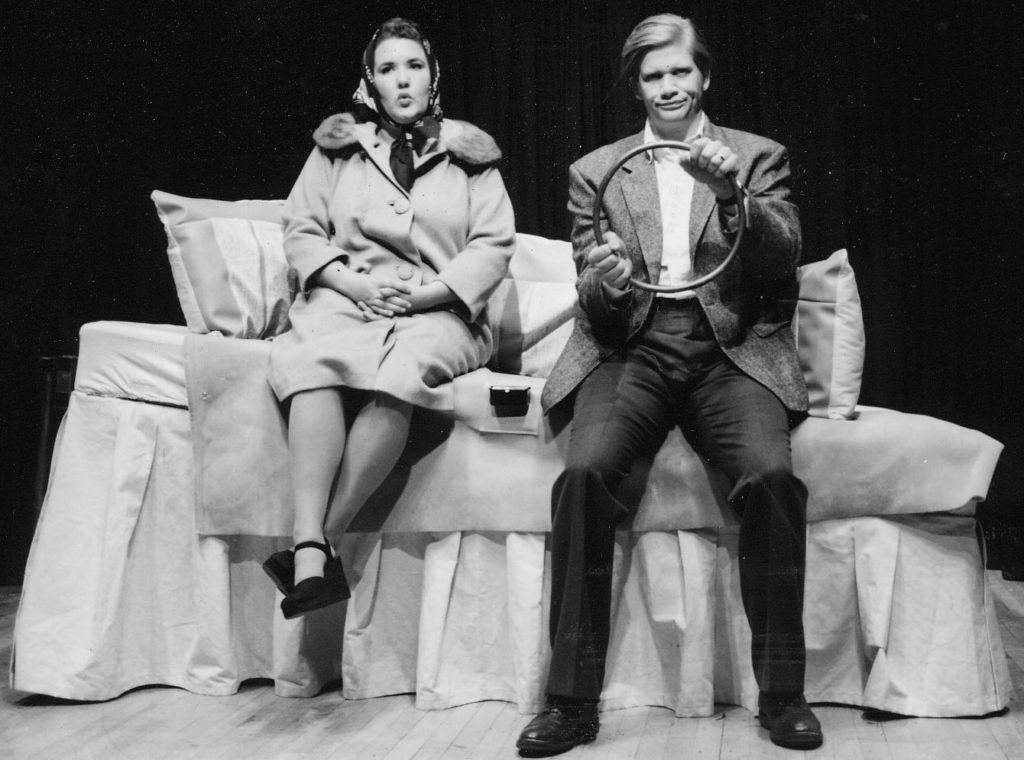

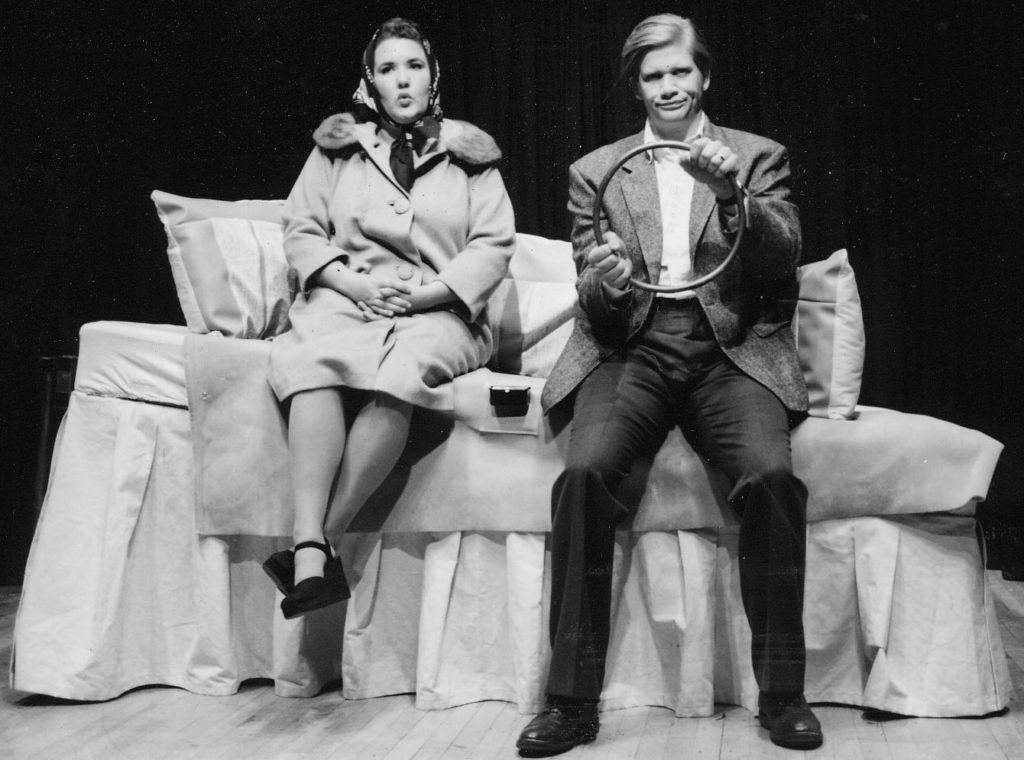

At the beginning of This Is My Significant Bother – which was Brian Colonna’s senior thesis – four actors are lying on a large bed, their left arms over the coverlet and perfectly aligned, each wearing a wedding ring. James Thurber didn’t have a very positive view of marriage. His men tend to be put-upon dolts and the women bossy harridans. The tone is slightly waspish, also sad and, in an understated way, very funny. The actors – helped by the music of the Hoagies, who play things like “Making Whoopee” and “Two Sleepy People” – have caught it perfectly, giving their portrayals a sort of stubby elegance.

A man kills a spider at his wife’s behest and then huddles under the covers, terrified by a flittering bat; a couple argues in their car about where to eat and whether Donald Duck is a more significant cultural icon than Greta Garbo; a husband decides to kill his wife so he can marry his stenographer, and the wife, having gotten wind of this, tells him exactly how he’s to do it; a divorced woman fills in her successor on all her ex-husband’s idiosyncrasies while he silently and meticulously makes up the bed. And there’s a touching story about a failed love affair, the sentences punctuated by silences and blackouts. If this is an early effort, you can’t help reflecting, it’s certainly a sophisticated one.

Cinderella is an extended piece of intense silliness, narrated by a be-rouged Evan Weissman in what can only be called Manglish; the rest of the cast speaks pure gibberish. The play begins when Cinderella’s sweet-faced mother (Erin Rollman) gives birth and almost instantly transforms into the Wicked Stepmother. She does this through a very clever costume change that forces her to walk backwards through the rest of the action. (Evil usually does occur when good is distorted or turned on its head, right? That’s why the word “sinister” is connected with left-handedness and the left side of things in general.) Doubling is a central theme in Cinderella. Both stepsisters are played by Hannah Duggan, wearing an asymmetrical wig and two different shoes. Erik Edborg, the tallest member of the troupe, is our heroine. He’s comforted in his sad predicament by his own left hand, which sings opera to him. When he’s dressed up for the ball, he’s represented by a simpering doll through another piece of costume magic. Weissman’s narrator becomes the Prince. The coach is signified by a pair of horses clipped to a hat, the importance of Cinderella’s leaving the ball by midnight emphasized by the clocks on the breast of her ball gown. “Your Feet’s Too Big,” the Hoagies sing helpfully, as an ugly sister tries to cram on that mythical slipper.

There’s no predicting what the next ten years at Buntport will bring, but we know they won’t be boring.

-Juliet Wittman, June 7, 2011, Westword

Buntport Theater has fun with one-acts and paper props

Now that Buntport Theater has come of age and is attracting reliably positive reviews and large, enthusiastic audiences, the six company members have revived one of their earlier works, an evening of one-acts titled 2 in 1. The first piece, “This is My Significant Bother,” is a dramatization of nine stories by James Thurber; the second is an explication of the Cliffs Notes explication of Beowulf (it makes sense when you see it — sort of). These are both slight pieces, but they’re clever and entertaining, and the sets and costumes are as inventive as ever. It’s pretty much impossible not to have a good time at Buntport.

As the evening begins, four actors — Brian Colonna, Erik Edborg, Hannah Duggan and Erin Rollman — are lying on a large bed, their left arms in perfect alignment on the coverlet, their hands conspicuously wedding-ringed. They manage to stay absolutely still as the audience arrives and settles in. Perhaps they’re asleep. One of the evening’s pleasures is the way the actors manage to move swiftly and soundlessly during blackouts, so that we’re always slightly surprised at where they’re each standing or sitting when the lights come on.

Although he apparently labored over their composition, Thurber’s stories are sketches rather than fully developed character studies or descriptions of events. They have the wistful, unfinished quality of his New Yorker cartoons, along with a misogyny so self-deprecating that it almost seems forgivable. If his women are all-powerful, soulless harridans, well, his men are pretty silly, too, and sometimes downright irritating. (Although, in a fable Buntport doesn’t attempt, it’s only the male of the species who’s capable of seeing a unicorn in the back garden.)

“Significant Bother” is not intended to be laugh-out-loud funny. It’s a sincere and gently humorous homage to Thurber.

A husband manfully protects his wife from a spider but cowers under the bedclothes when he hears a bat. A woman stands up in court and insists she deserves a divorce because of her husband’s habit of holding his breath. In one of the most absurd and amusing pieces, a police officer finds a woman seated in a car while a man crawls on the ground in front of the vehicle; they are trying to ascertain whether a human being’s eyes will glow in the headlights as a cat’s or dog’s would. In another car scene, this time inside the car, a couple fights over whether Greta Garbo is a more important cultural icon than Donald Duck and bickers about where to stop for a hamburger, the wife insisting that the eatery must be a cute one. Meanwhile, the car is emitting a threatening and unidentifiable noise. Yet another husband orders his wife into the basement so that he can kill her and make off with his stenographer. Wise to his plan, she gives him orders on how to accomplish the deed. All of this is interspersed with interesting renditions of such ’30s songs as “Makin’ Whoopee” and “Happy Days Are Here Again.” And the bed that anchors the play (in the very last scene, a man painstakingly smooths the sheets while his ex-wife discusses his failings with his wife-to-be) is manipulated by the Buntporters with their usual sangfroid, becoming by turns a car, a platform, even a cellar.

Perhaps the most interesting and unexpected piece is a mood story about a doomed love affair called “Evening’s at Seven,” which is told through a series of lighted tableaux separated by patches of darkness. It’s touching, original and sophisticated.

For the second play, the cast appears in front of a backdrop of text wearing dark-blue maintenance men’s outfits and tool belts that hold an arsenal of paper props. They proceed to act out the story of Beowulf, interspersing the action with textual commentary — and their own acerbic comments. In case you’ve forgotten, this Old English poem concerns the predations of a monster, the monster’s dam (or, as the Buntporters have it, “dam mother”) and a dragon. As always, the props are inventive; in this instance, they’re made entirely of paper. Beowulf’s army consists of a string of paper cutouts worn across Edborg’s chest like a bandolier; streams of paper representing blood from a wound are helpfully and multiply labeled “blood,” just as the paper crown bears the legend “crown.” The paper dragon is a thing of wonder. Periodically, we hear a voice reading from Beowulf itself and — though you’d need to know Old English to understand the words — the power and beauty of the text makes itself felt through all the loony shenanigans.

The acting is terrific, as always, though it concerns me a little that both Colonna and Edborg act so much from the neck upward. I’d like to see their voices and impulses coming from deeper in the body. In addition to the cast, Matt Petraglia, SamAnTha Schmitz and Evan Weissman helped create 2 in 1.

I’m getting tired of saying this, but if you haven’t attended a show at Buntport yet, you should. You won’t see anything like it anywhere else.

-Juliet Wittman, May 6, 2004, Westword

THURBER’S RELATIONSHIP STORIES

A period show based on nine short stories by the marvelous James Thurber. (more…)

Buntport brilliant in reprise of ‘2 in 1’

You Buntport-come-latelies will want to hie yourselves over to Lipan Street and see how it all began, as the seven-person collective resurrects its second show. With the two one-acts that make up 2 in 1, Buntport reveals that its group’s amazingly cohesive aesthetic emerged full-force, like Venus from the half-shell, wearing a Groucho mask.

The two works together also demonstrate the breadth of Buntport’s abilities, from wry ’30s charm to a postmodern spoof that provokes such deep guffaws smokers may want to take precautions.

In . . . and this is my significant bother, the short stories of James Thurber are adapted into vignettes drawn with the light touch of one of the author’s own New Yorker cartoons. Each one tackles the foibles of marriage from its own angle, with the actors in superb period performance.

Brian Colonna personifies the meek, retiring and henpecked husband. He preens with macho pride after swatting a spider, then cowers from a bat. In another story, after falling in love with his secretary, he informs his wife of his plans to kill her, his voice squeaking like a bad hinge. Then he capitulates as the wife dictates exactly how and when the murder will occur.

Erin Rollman’s Betty Boop eyes and Clara Bow lips are a fast-track back to the ’30s, as is a falsetto voice that cries out screwball. In a scene where others voice their thoughts, both she and Colonna perfectly embody the facial tics of a busy brain.

Hannah Duggan, frequently severe or frumpy here, can browbeat without being hateful, and Erik Edborg turns the leading-man image on its ear.

It’s a journey back in time from Thurber to Beowulf, but Act II’s Word-Horde is hilarity of the postmodern variety. Using words in the most ingenious ways as costumes, props and set, they offer up a Cliff’s Notes version of the Anglo-Saxon epic poem that has been the downfall of many a high school freshman.

Not an opportunity for humor has been missed here, but none of it is superfluous or comes at the expense of the actual tale of Beowulf. Massive sections are dramatized in summary (don’t miss the human boat or bloody attack on Grendel), followed by pithy “commentary,” aided by a checklist of themes and symbols.

It’s not imperative that you have read Beowulf; it’s only necessary that you have attended school to appreciate the sublime humor of the piece.

Offstage, the four actors are supplemented by Matt Petraglia, Samantha Schmitz and Evan Weissman. In this seemingly anarchic environment, a solid company has emerged that devises the most brilliant of visual and sonic effects, always remembering that theater should enlist multiple senses.

-Lisa Bornstein, April 30, 2004, Rocky Mountain News

Adjectives that would seem like useless hyperbole anywhere else often find their legitimate homes when referencing Buntport Theater’s work. The young collective presenting original works on Denver’s Westside really is uniquely talented, madcap with energy and originality, and, as some have said, “genius.”

But nobody’s perfect.

Buntport’s latest excursion is the old-school “2 in 1.” It’s a throwback on multiple levels, but mainly because Buntport performed the two original one-acts in 2001.

Remounts are good business when you’re Buntport and always attracting new audiences to your mainstage productions and the excellent, biweekly “Magnets on the Fridge,” which closed for the season last week. It gives newbies a chance to see the work that made the company what it is today.

But Buntport has moved forward and, dare I say it, matured a lot in the three years since these were first produced. The interim has seen multiple self-written and -directed full-length plays, one-acts, “Magnets” episodes and at least one musical for this company, one of the busiest in town. So reaching back into their short history has to come at a sacrifice.

Act one is “… and this is my significant bother,” the Buntporters adaptation of some of James Thurber’s short stories. They attempt to explore the American humorist’s literary world, which is full of insight into both relational psychosis and the mind of the individual Everyman in mid-20th century America. Although the series of stories operates partly on Buntport constants (including an excellent multipurpose set and the use of different storytelling voices), it doesn’t always hit.

The theater company is obsessed with style and period and varying their stories’ approaches whenever they can, so this – subtle scenes involving couples in bed, kneeling in front of a running car, or amid awkward conversations about loving and longing – is Buntport’s tribute to the America of “New Yorker” cartoons in the ’30s and ’40s.

And it’s fair to say that this style doesn’t work as well for Buntport (and its core audience) as, say, the detective aesthetic of the ’40s – the setting of their tight, seriocomic “McGuinn and Murry” – or the Elizabethan era that was home to its spoof on Shakespeare, “Titus Andronicus: The Musical!”

They hit most clearly in one short where Brian Colonna’s aloof husband tells Hannah Duggan’s hard nosed wife of his plans to kill her and marry his stenographer. “No, I’m not going to bed,” he quips toward the end. “I’m going to bury you in the cellar.” It’s the least subtle of the pieces, but it’s also the one that clicks on levels that venture beyond the players psychoanalyzing simple-minded, nostalgic, Rockwellian images.

They get closer to comfort with act two, “Word-Horde: A Dramatization of the Study Guide to Beowulf,” which could be called “Compleat Text of Beowulf (Abridged).”

With the help of an ominous, omniscient voiceover acting as the voice of reason, the four Buntporters (Colonna, Duggan, Erik Edborg and Erin Rollman dressed in black and yellow mechanics scrubs, an homage to Cliffs Notes) act as the Everyman student circa 2004, mumbling obscenities and frustrations underneath faux-sneezes as they work their way through the text line by line … almost.

Like “Titus,” “Beowulf” lends itself to the self-deprecating, fast-talking production style. It’s olde, wild and weird, and the Buntport players – whose outlandish writing is more concise and pointed here than in the first act – seize every opportunity to poke fun at the book and themselves.

They perform against the backdrop of an enlarged version of the aged text. Props and costumes made of paper, handily attached to their tool belts, help move the story forward. And the audience gets a treat – we’ll call it Buntport spectacle – when it comes to the dragon at the end of the story.

The two shorts work better as a pair than they would work alone. The night gets off to a slow start. But it builds with Buntport’s incredible attention to detail, such as Duggan’s tuning the car radio in the first act, a pantomime timed perfectly with the audio. And it closes with a laugher.

Not genius, especially when held up to their previous work. But still not a bad night of theater.

-Ricardo Baca, April 30, 2004, Denver Post