Just imagine if Buntport Theater had Eugene O’Neill’s ego.

Why, the world would be theirs.

If “The 39 Steps” can play for two years on Broadway, think how warmly a national audience might embrace the smart, quirky little inventions Buntport turns out four times a year in their little warehouse on Lipan Street.

Lucky for us their ambitions remain so humble.

Their latest, “The World Is Mine,” plays out inside the mind of America’s greatest, most damaged dramatist as he recovers in a hospital from an appendectomy. O’Neill is just getting started on “Long Day’s Journey Into Night,” the play he wrote to be his epitaph: a bleak, boozy look back at his messed-up childhood.

Sickness underlines “The World Is Mine,” mostly of the self-inflicted or indulged variety. But it was in actuality sickness – specifically recovery from a nasty bout with tuberculosis – that turned a young, derelict O’Neill to writing in the first place. That, in essence, makes “The World Is Mine” as much about creation as disease. Even if writing can be equally consumptive.

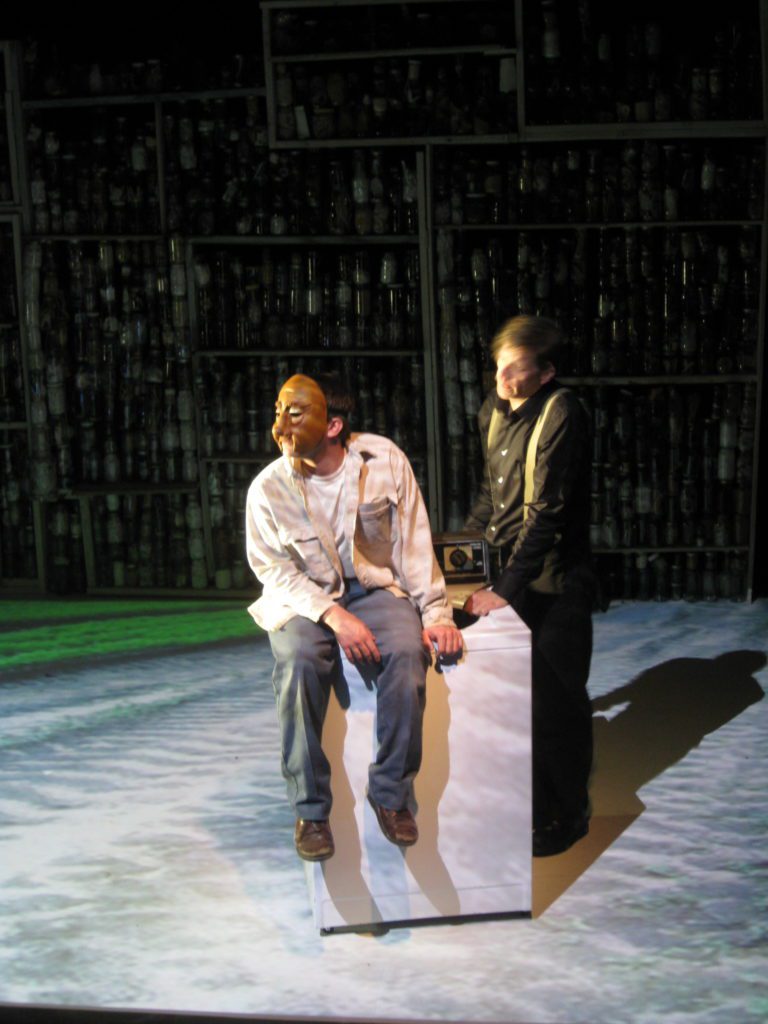

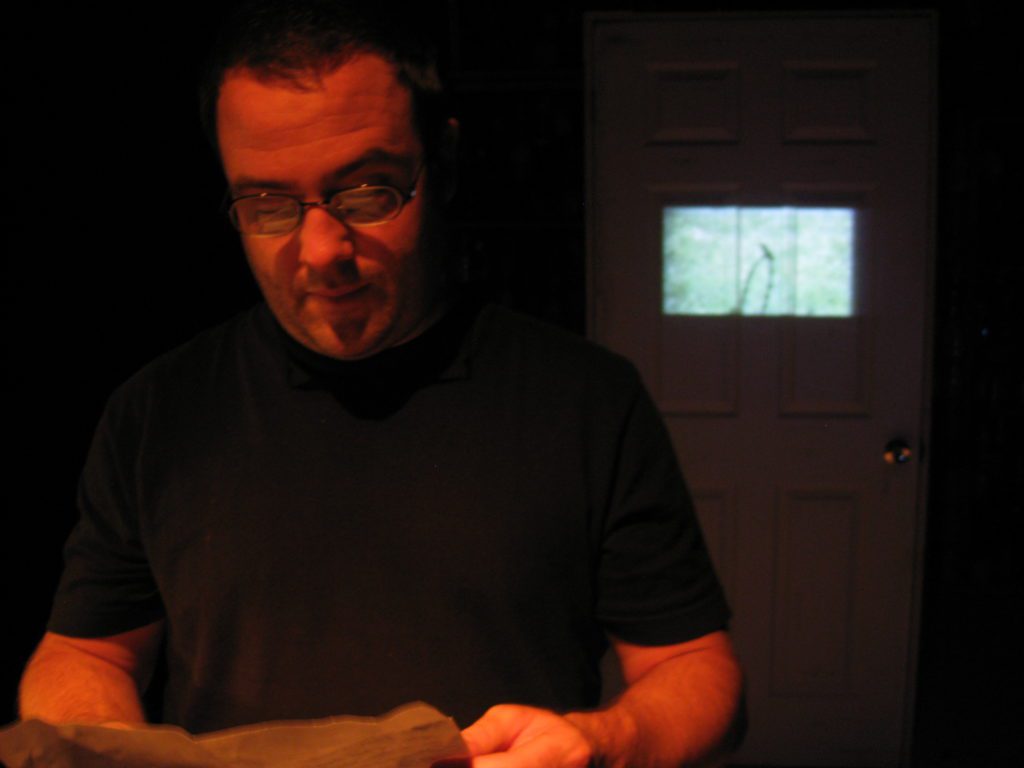

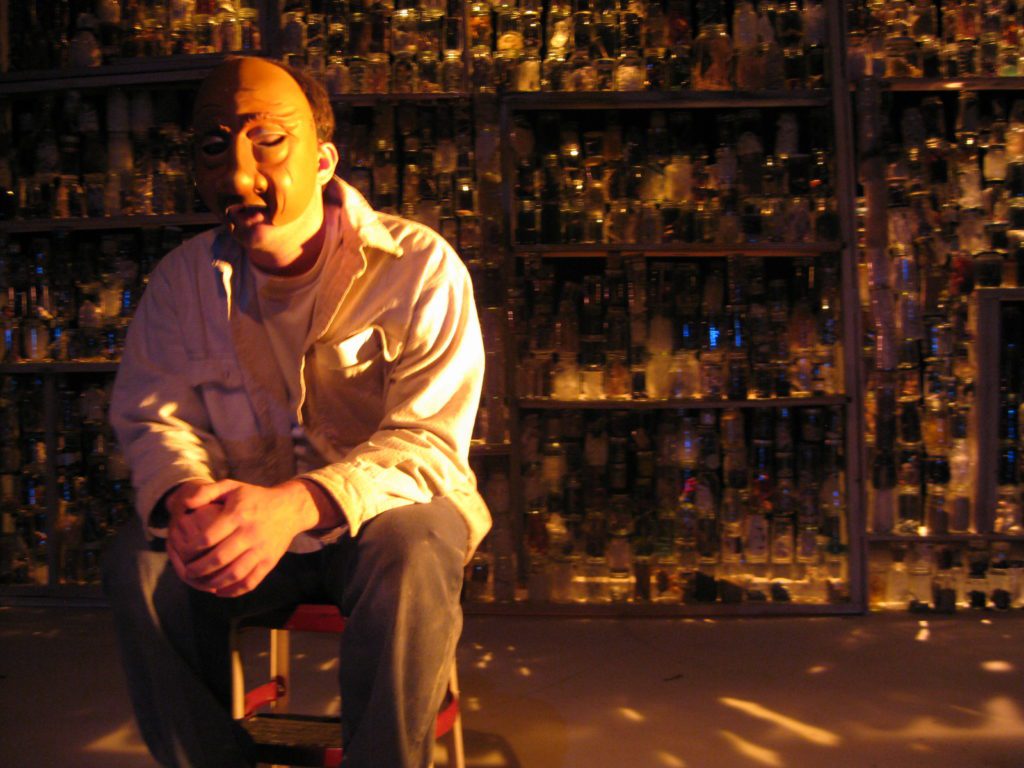

We open in O’Neill’s living room in Connecticut – as the patient remembers it. A furrowed Erik Edborg, as O’Neill, enters with a hospital gown covering a business suit. He’s setting the scene for “Long Day’s Journey,” and he hasn’t quite settled on the floor plan. So there are duplicate set pieces. A lamp might yet go here – or there – so, for now, they exist in both places. Lights turn on and off with a flick of his finger.

He’s narrowing things down.

O’Neill was consumed with the complex psychology of his characters, and “The World Is Mine” turns out to be a fanciful and elucidating examination of his own inner workings. He doesn’t just simply conjure the ghosts from his masterpiece – his nomadic actor father or morphine-addicted mother. He does what all whiskey-soaked brains do: He intermingles past and present.

So a nurse reminds him of the daughter he never saw again after she ran off with Charlie Chaplin at age 18, but still lives perpetually in his subconscious. A Swedish emissary who has come to deliver O’Neill’s Nobel Prize reminds him of the disintegrating brother who came to viciously resent his sibling’s success.

These visitors at times become their doppelgangers, most devastatingly when the affable Swede (Brian Colonna) suddenly delivers a scathing attack on O’Neill that doesn’t so much pierce the writer but send him scrambling for a pen.

In one of many delightful twists, O’Neill is both inspired and tormented by his coquettish third wife, Carlotta (a wonderful Erin Rollman), the provocateur and collaborator who shares both his mind and hospital room (she’s been admitted for nerves).

Buntport, well-known for its whimsical staging conceits (Let’s just say they give new meaning here to an “Irish coffee table”), most cleverly illustrates O’Neill’s pathological self-absorption. The women wear mustaches that mirror his own. Not only does O’Neill’s adult portrait now hang on the wall of his childhood home, there are two facing versions of it (Who can decide on one’s best side?). All these characters are merely variations of O’Neill himself.

Of Buntport’s more than two dozen original productions, “The World Is Mine” is easily among its best-acted and written. O’Neill’s life was so absurdly laced with tragedy, including suicides by two erudite sons, it would be easy to almost lampoon it.

Instead, the play is melancholy and earnest down to its wonderful title. It’s a line Edmond Dantes yells in “The Count of Monte Cristo” – a role that defined and haunted O’Neill’s actor father. He said the line 6,000 times and didn’t once mean it, O’Neill says. He considered his father a condemned man, “doomed to live life as the same person.” Just like the rest of us.

O’Neill single-handedly changed how we think about theater. And Buntport, collectively, is doing the same thing.

“The World Is Mine” is a prescient introduction to “Long Day’s Journey,” which the Paragon Theatre will also be presenting, opening Feb. 13. Together, they will make for terrific companion pieces

-John Moore, February 4, 2010, Denver Post